Aetius

Council of European Canadians

April 12, 2015

Montagu and the Race Question

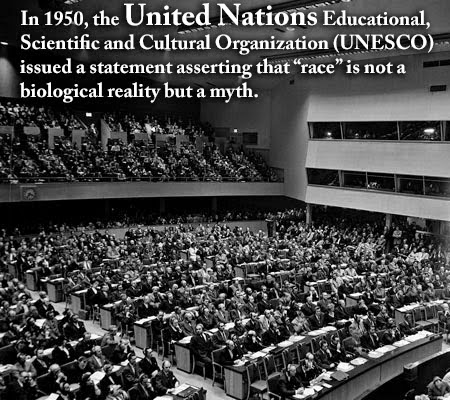

Discrediting the concept of race was an obsession for Ashley Montagu, born Israel Ehrenberg (1909-1999). His PhD in Cultural Anthropology was supervised by Franz Boas. After publishing in 1940 Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race, Montagu came to be seen in the United States as a leading expert on human variation. In 1950, he was appointed investigator for the UNESCO statement “The Race Question”. This statement, released in 1950, argued that, “for all practical social purposes ‘race’ is not so much a biological phenomenon as a social myth.” It also stated that WWII was made possible by the idea that mankind is divided into different races.

This statement resonated with confidence the belief that science was on its side and should be employed to discredit the concept of race. The knowledge already acquired in the social and natural sciences, “made possible [through] extensive inquiries and experimental research”, had established that “it is impossible to demonstrate that there exist between ‘races’ differences of intelligence and temperament other than those produced by cultural environment.” The concept of racial differences,

instead of being based on scientific facts, is generally maintained in defiance of the scientific method. As an ideology and feeling, racism is by its nature aggressive. It threatens the essential moral values by satisfying the taste for domination and by exalting the contempt for man.

It claimed that the “scientific material available to us at present” teaches us that “the one trait which above all others has been at a premium in the evolution of men’s mental characters has been educability, plasticity.” The statement called upon UNESCO to start a campaign everywhere to spread the “truth” about race. It said we must learn from scholars:

exactly why and how social, psychological and economic factors have contributed in varying degrees to make possible the [racial] harmony which exists in Brazil.

An earlier version of this statement had sparked a controversy, resulting in some revisions before it was released in 1950, with subsequent revisions in later years. There was disagreement over the fact that non-scientists, sociologists and anthropologists, had been the main consultants in the formulation of the first version of the statement, and yet the statement insisted that “the competence and objectivity of the scientists who signed the document in its final form cannot be questioned”. If the statement was to carry real authority, it needed to be signed and agreed upon by real experts, “biologists, physical anthropologists”, who know about the genetics of race.

Scientists were also unsatisfied with the claim that there was no evidence for differences in intelligent tests; they wanted a change in the wording to the effect that such differences had been observed in tests but that there was no scientific evidence to believe that they were innate; they were the result of cultural influences and levels of education.

There is reason to believe that Montagu was not happy with the edited version for he had been arguing, since the early 1940s, against the use of the term “race” itself, calling for its replacement by the term “ethnic groups”. He wanted the word “race” to be taken out from the vocabulary of science. But scientists were reluctant on the grounds that the term “race” was still useful in designating groups characterized by certain concentrations of hereditary traits, which, in the words of the statement finally released, “appear, fluctuate, and often disappear in the course of time by reason of geographic and or cultural isolation.” Races were biologically real even if there were not substantial innate differences between them.

The Race Question Today

Nevertheless, Montagu’s effort to categorize people by ethnicity rather than race is now the accepted norm in the social sciences, and not only for the reason that labeling people with such broad categories as “White” or “Asian” leave out multiple ethnic groups included within each of these races, cultural traits such as language, national origin, and religion, but also because there is a consensus that race is a social construct. This is the official position of the American Sociological Association and the American Anthropological Association. These associations reject the biological and genetic basis of racial classification. However, both these associations have released statements on the “Importance of Collecting Data on Race”. The ASA justifies this collection of data on the grounds that there is racism in Western societies, unequal opportunities and achievements for racial minorities, which needs to be measured in order to equalize results and finally do away with the concept of race.

The purpose of the ASA statement is to support the continued measurement and study of race as a principal category in the organization of daily social life, so that scholars can document and analyze how race — as a changing social construct — shapes social ranking, access to resources, and life experiences.

The statement makes reference to new medical findings showing that African Americans have a higher rate of prostate cancer, and arguing in favor of this medical difference, for how else are sociologists going to make the case that African Americans suffer more from this illness due to unequal chances for nutrition and a “higher likelihood of living near toxic waste dumps”?

In fact, the natural sciences have taken a similar view. For example, an editorial of New England Journal of Medicine, a very prestigious publication, declared in 2001 that “race is a social construct, not a scientific classification”. What is interesting is that this journal felt a need to make this statement in light of an accumulating series of finding demonstrating that different races exhibit different genetic patterns of disease and drug response. They know it would be inconsistent with the medical profession to ignore findings pointing in the direction of better diagnosis and treatment.

Among some critics of cultural Marxism there is this wishful supposition that the science of genetics is bound to undermine politically the basic tenet that all races are equal and the consequent political view that white racism combined with “bad” cultural influences are the main culprits for the persistence of racial discrepancies. But this concept is a central pillar of the entire cultural superstructure of Western society. The fanaticism that drove Montagu to say that race “is an area in which one must never let up, for the racists are ultimately the only genuine enemies of humanity” is even stronger today than in the 1950s. The pursuit of racial harmony through diversification is inherent to the establishment. This establishment has a wide net set to capture the “enemies of humanity” even if such enemies would prefer a world with racial diversity and ethnic self-determination rather than racial convergence and inevitable racial ranking inside the West.

However, if the 1950 UNESCO statement on race was able to align the science of the time with the notion of racial equality in a relatively easy way, the growing identification and mapping of the genes of the human genome is creating difficulties requiring new intellectual efforts beyond the mere repetition that education against prejudice can overcome current racial variations.

Integrating Cultural Marxism and the Science of Psychology

The establishment has not choice but to come up with novel ways of integrating new genetic findings into cultural Marxism. My previous article, The Ethnic Phenomenon in Psychology, covered some of the ways in which psychology has fully assimilated genetics and evolutionary theory while remaining committed to the basic precepts of cultural Marxism when it comes to such issues as prejudice, IQ testing, in-group favoritism and out-group derogation. This discipline is not only very comfortable with the latest research in genetics but may well be at the forefront in the employment of science to serve the goals of diversity. Psychology has cultivated a number of perspectives including “social constructivism”, which recognizes the way culture influences the way people view the world, following proper methodologies. It has developed subtle strategies balancing out different perspectives, tilting the text in a strong “culturalist” direction when it comes to race and prejudice, but then tilting the text back in a strong “genetic” direction when it comes to other behavioral traits having to do, say, with cognition, memory, illnesses, anxiety.

Karen Huffman’s Psychology in Action (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Ninth Edition, 2010), for example, explicitly announces in the Preface its “strong scientific basis and vast depth and breadth”, while posing the following question in the very next sentence: “Did you notice the happy, life-filled people pictured on the cover of this book?” The image on the cover is of a black guy dancing with a white girl. “We chose these photos to reflect our ‘Living Better with Huffman’ theme.” The text utilizes the scientific concepts of “operant conditioning” and “cognitive-social learning” to propose environments in which Westerners from childhood onward will experience “negative reinforcement” when they behave in prejudicial ways, and “positive reinforcement” when they behave in ways “appropriate” to a diverse environment.

Karen Huffman’s Psychology in Action (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Ninth Edition, 2010), for example, explicitly announces in the Preface its “strong scientific basis and vast depth and breadth”, while posing the following question in the very next sentence: “Did you notice the happy, life-filled people pictured on the cover of this book?” The image on the cover is of a black guy dancing with a white girl. “We chose these photos to reflect our ‘Living Better with Huffman’ theme.” The text utilizes the scientific concepts of “operant conditioning” and “cognitive-social learning” to propose environments in which Westerners from childhood onward will experience “negative reinforcement” when they behave in prejudicial ways, and “positive reinforcement” when they behave in ways “appropriate” to a diverse environment.

In a chapter on “learning” and “conditioned race prejudice”, which contains numerous pictures of white racists, three white students with the sign “We wont go to school with Negroes”, a little white girl holding a KKK sign, and a white killer of James Byrd, “viciously murdered because of his skin color”, as well as of a “humanitarian” named “Mohammed”, Huffman promises students that the chapter will teach them to “expand their understanding”, “control their behavior”, “improve the predictability of their lives”, “enhance their enjoyment of life” and help them “change the world!” (202-239). This text is still going strong with a tenth edition released to great acclaim. Psychology is by far the most popular discipline in the Arts.

Symposium on How to Reconcile Biological Anthropology and Cultural Marxism

Another example of this effort to accommodate new scientific findings while maintaining the essential principles of the UNESCO statement on race is a symposium held in 2007 at the University of New Mexico entitled “Race Reconciled?: How Biological Anthropologists View Human Variation”. An article on this symposium was published in American Journal of Physical Anthropology (2009) under the same title. Attended by specialists in human biology, genetics, forensics, bioarchaeology, and paleoanthropology, the goal was to get these experts to think about

- the way recent scientific findings were affecting their views on human origins, relationship between biology and culture, forensic identification, and “whether or how to use the term ‘race’ in research and teaching”; and

- to identify common ground and points of disagreement.

There were “many participants”, with ten articles in total produced by some of the participants in this issue of the AJPA. Should we be surprised that the “common ground” reached on the concept of race was consistent with the views held by Montagu, and the other members of the Bolshevik triumvirate, Stephen J. Gould and Richard Lewontin? They agreed that:

- There is substantial biological variation among individuals within populations.

- Patterns of within- and among-group variation have been substantially shaped by culture, language, ecology, and geography.

- Race is not an accurate or productive way to describe human biological variation.

The second point can be consistent with the principle of biological variation since Darwinian evolutionary theory includes as a matter of fact the role of the environment in shaping biological variation between racial groups, and, as we will see in a future article, culture has been a major part of the human environment not only affecting but accelerating genetic changes among human populations. BUT what was agreed here was that the variations in levels of development and intelligence we observe between groups today have been substantially shaped by the geography and culture in which children have grown.

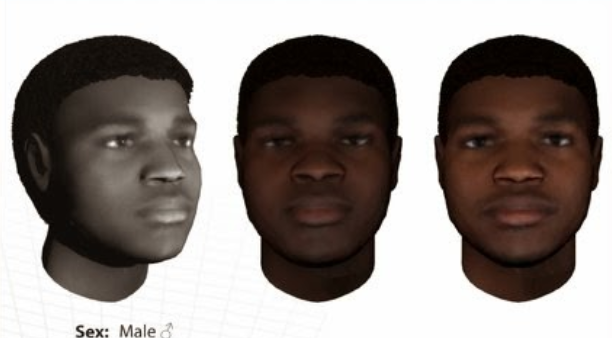

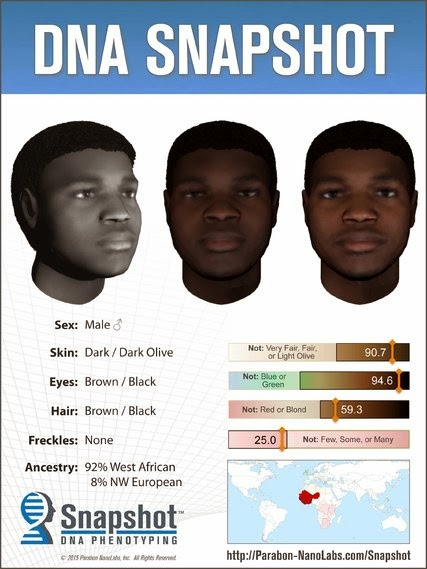

Participants also debated “sources of disagreement.” It becomes apparent in reading about these disagreements that, having shown their common acquiescence to the political expectations of their times, they had to find a way to sustain the authority of the science of genetics and what it teaches about group variations “in the social and health-related” fields, for example. Race is a social construct, but should “racial categories” be rejected altogether “in medical genetic research”? There was “one fundamental disagreement…which was over the precise nature of the geographic patterning of human biological variation.” Essentially this disagreement was over how to express this variation without using racial categories.

Some argued point blank that “there are no geographic discontinuities and therefore no races.” But others “suggested that geographic patterns of human genetic variation are the result of a complex combination of population splits, regional founder events, and local migration.” In other words, there is genetic variation between population groups; so, as the title of the symposium indicated, how do these scientists “reconcile” this empirically based research on variations with the rejection of the concept of race? Rather revealingly, they write about how scientists are “strongly influenced by introductory textbooks” and why the ideas of Lewontin in these texts led them “to a rejection of biological race concepts”, but these texts, they now complain, “seldom address the results of more recent and novel studies of human biological variation that reveal a more complex population history” than the mere rejection of race categories would have students believe. It looks, then, like introductory texts in the sciences are hiding recent research in genetic variation, still teaching their students the ideas of Montagu and Lewontin. These texts “seldom consider” the “medical genetic significance” of the “study of human biological variations”.

The wording is rather convoluted as these participants struggled to reconcile their research findings with the ideas of Montagu, and, in the end, the impression given is that they reject the concept of race, “its pernicious social consequences”, while accepting the idea that there are significant genetic variations in human groups distributed in different geographical locations with important medical and theoretical implications.

What rhetorical shapes and serpentine expressions will these reconciliations between science and cultural Marxism take as the science of genetics keeps piling on evidence against the notion that there are no substantial genetic variations between human groups? Don’t count on any concessions; the entire educational institutional network of universities, schools, government funding and scientific centres is committed to Montagu’s Brazilianization of the Western world in the name of “racial harmony”.