Silas Reynolds

The Right Stuff

August 5, 2016

I’m not planning on seeing the remake and thoroughly diversified The Magnificent Seven, a film directed by the highly overrated Antoine Fuqua, one of Hollywood’s Magic Negro directors. Everything is a remake, or–in a particularly merchant-type way–a story is “reimagined.” It’s also painfully obvious, even for some normies that are waking up, that everything that was once White (implicit and/or explicit) must be methodically diversified, which really means less White. I’m not wapanese or a weeb, so I don’t consider Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 Seven Samurai the “original,” but feel free to debate that amongst yourselves; I’ll admit that it is a good film though. The original American The Magnificent Seven was explicitly White, with all of the seven fictional protagonists identifying as the bane of the Left–straight White males. Hell, the villain in the original was even played by a Jew–the great (((Eli Wallach))) (excellent as the malcontent and permanently soiled Tuco in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly).

The plot of the original 1960 version is fairly straightforward: our White heroes must save a Mexican village, severely lacking in basic survival agency, from sloppy high-time-preference mestizo bandits (a somewhat similar theme in The Wild Bunch–Mexicans in the 1960s and, to a degree, even today are depicted as no-account drunken fools). The heroes are: Yul Brynner (not Jewish, and superb as the antagonist in Michael Crichton’s 1973 Westworld), the consummate vigilante Charles Bronson (also not Jewish, although the kikes claim he is a member of the tribe), real-life bad boy and womanizer Steve McQueen, Cross of Iron alum James Coburn, based Serb Brad Dexter (born Boris Michel Soso), Horst Buchholz (who plays a Mexican in the film) and the original The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Robert Vaughn. The original film was selected for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being, “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.” So, naturally, it has to be pozzed and destroyed by modern Hollywood.

The remake will include everybody’s favorite movie dindu nuffin, Denzel Washington, as the leader of the seven. Chris Pratt (who may save this film), Ethan Hawke and Vincent D’Onofrio are also members of the group. For pozz purposes (other than the ridiculous idea of a dindu leading White men in the Old West), the film will include a railroad worker (Lee Byung-hun), a beaner (Manuel Garcia-Rulfo) and, perhaps most laughably, a Comanche warrior (Martin Sensmeier)–because everyone knows the Comanche were keen on saving small towns. The strong wymyn trope is included as well. And finally, the villain is a White male–big surprise. In the Current Year, you can guess the plot, sub-plots, characters, etc. all without even watching a film. The Jews in Hollywood really are that lazy. They never innovate, they only replicate–over and over and over again.

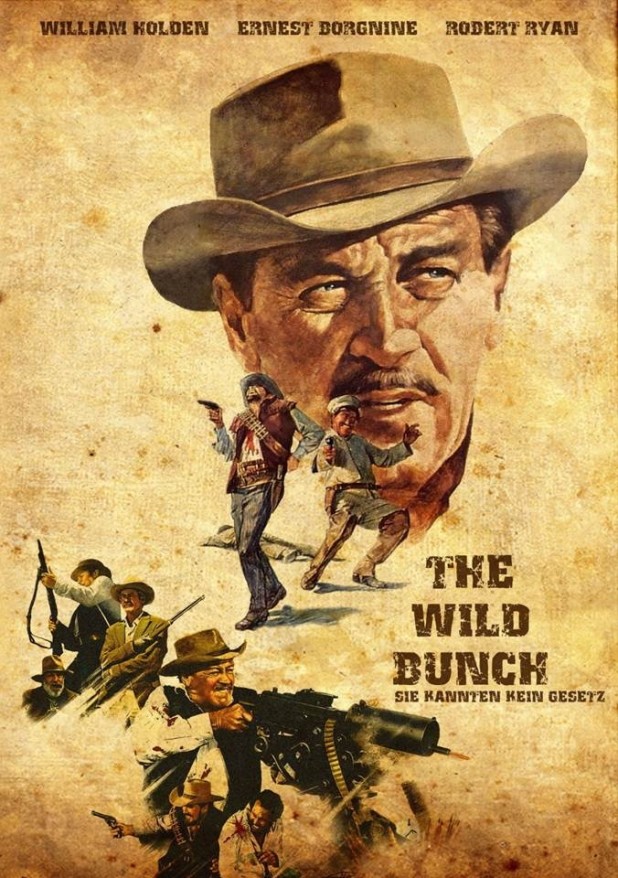

But the 1960 The Magnificent Seven was never very high on my list of great Westerns–still, a respectable film to be sure. It’s a shining example of the early 1960s, safe and clean, with established heroes, straightforward plot and clear-cut villains. By 2016, the film really doesn’t hold up to repeat, or even initial, viewings. The polar opposite of that film, and the much stronger film, is 1969’s The Wild Bunch. Directed by the innovative Sam Peckinpah (highly recommend his visceral beta-to-alpha awakening, Straw Dogs, and cult classic Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia), The Wild Bunch seems to mirror the decay and creeping nihilism of the late 1960s. In the film, there are no “heroes” in the white hat; they’re barbaric whore-chasing trash with a penchant for graphic violence–and I do mean graphic, especially for 1969. The Wild Bunch includes all the trappings of a top-tier Alt-Right film: mestizo whores used as human shields, child soldiers, proto-SJWs (Temperance League) getting trampled to death, the proper usage of a Browning M1917 and a beaner body count so high that it may even match the Duke’s The Alamo.

A revolutionary technique for 1969, The Wild Bunch is noted for its multi-angle, quick-cut editing and use of normal and slow motion images. Like The Magnificent Seven, Peckinpah’s film was also selected for preservation in the Library of Congress for its cultural, historical and aesthetical significance. Peckinpah’s goyish genius really can’t be underestimated–he filmed the two critical shootouts with six cameras operating at different film rates, including 24, 30, 60, 90 and 120 frames per second. He also shot over 300,000 feet of film from 1,288 different camera set-ups, requiring him to stay an extra six months in Mexico (presumably, he also enjoyed wine and women while there–he would have fit in well with his protagonists, based on his personal life) for editing. His film set a record for more edits—3,643—than any other Technicolor film up to 1969. Supposedly, more blank rounds (90,000) were discharged during the production than live rounds were fired during the Mexican Revolution in 1916 (the film is loosely based around this time period).

Our protagonists are led by the hunted and haunted Pike Bishop, played by the aged and weary William Holden (excellent in The Bridge on the River Kwai). The film opens as his band of outlaws, disguised as members of the U.S. Calvary, ride into the Temperance League-infested town of Starbuck. They think it’s the perfect guise to rob a bank, but really, they’re being set-up by bounty hunters, funded by corrupt railroader (they all are in any Western) Harrigan and led by Pike’s former partner, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan). A merciless shoot-out erupts, wounding and killing countless innocent bystanders (including men, women and children) and sending Pike’s crew on the run with the bounty hunters following them. The first ten minutes is brutal and breathtaking, much like the finale.

Thornton’s pursuit is personal, as he wants to avenge a past betrayal by Pike that landed him in prison. Yet, deep down, the viewer gets the sense that Thornton wishes he were back with his old crew, and thus laments chasing a group he secretly admires. In the end, we see what Thornton really missed was the camaraderie of men, not the trash bounty hunters his saddled with throughout the chase.

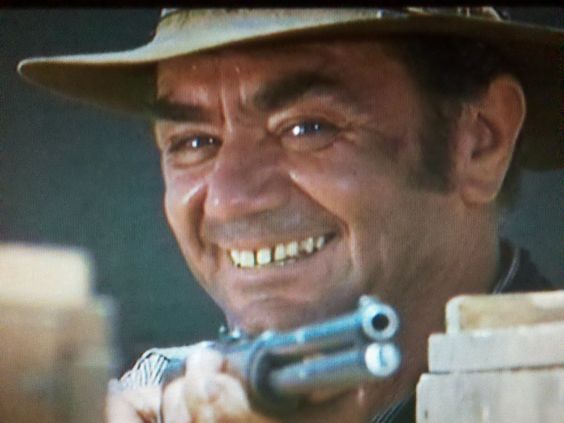

Additionally, the crew that make up of “The Wild Bunch” are all admirable actors. Pike’s loyal sidekick, Dutch, is played by the always solid Ernest Borgnine (exceptional in the underrated cult classic The Poseidon Adventure). The Gorch brothers are rough-housing scoundrels portrayed by Warren Oates and Ben Johnson (they played each other’s nemesis in the acclaimed John Milius’s film Dillinger). Finally, there’s Angel (played by journeyman actor Jamie Sanchez)–whose loyalty to his tribe (revolutionary mestizo peasants) acts as a catalyst in propelling the crew to their eventual fate.

They are a group of men playing by their own rules, sharing an ample supply of laughs, booze and cheap women. Modernity is the problem, however. The crew has yet to adapt to 20th-century America. Their answer? Delay the unescapable by crossing the border and pulling jobs during the volatile Mexican Civil War. Pike says, “We’ve got to start thinking beyond our guns. Those days are closing fast.” The Bunch live by an anachronistic code of honor without a place in 20th-century society. Within 15 years, Holden, Ryan and Peckinpah had all died, bolstering the film’s theme of dying outlaws.

But the most influential theme is represented by the symbolism of the scorpions and the ants (symbolism that should be familiar with any member of the Alt Right – the numbers game). The film’s opening title sequence is a montage of Pike’s crew marching into Starbuck. Along the way, they pass some children (male, female, white and brown) who are watching a handful of scorpions fight millions of small ants. It is a telling example of a superior (and individualistic) power overwhelmed by a horde of mindless opponents.

I am not a believer in scrutinizing films (or novels) for symbolism, as it is the purview of shitlib college professors to “psychoanalyze” everything in film and literature. However, sometimes analysis of symbolism cannot be denied. In The Wild Bunch, we see the children laughing and grinning as they place the scorpions into a swarm of ants. The children later set both the ants and scorpions ablaze. The scorpions represent Pike’s crew, who themselves represent both lawlessness and advanced middle age. The ants represent the public, who seek law and order. The fire stands for the coming of a new age, that of the automobile and the end of the Old West. The children are the next generation, who will thrive in the new order, but will always preserve the cruelty of the past.

The finale’s death toll is immense (well over a 150 killed in the last ten minutes), and is punctuated by frequent cut-aways to women and children, many of whom become collateral damage (some deservedly cut down by the outlaws). The scorpion symbolism becomes less abstract and more actual towards the end of the film–instead of battling modernity, we see the “bunch” battling an army of inferior (truly–they’re portrayed as grimy sub-humans) Mexican soldiers. Loyalty to their “tribe,” that’s what sends Pike’s men towards their own fateful and ultra-violent Götterdämmerung (or “twilight of the gods”).

This is a masterpiece in the Western genre. I give the film a complete five stars. If you haven’t seen it, you must watch the original director’s cut, as the studio jewed Peckinpah’s original creation–no kidding, unbeknownst to Peckinpah, (((Warner Bros.))) brought in (((Phil Feldman))), who cut ten minutes from the film, making the plot almost incomprehensible.

PS. The look of abject horror on the faces of the drunken Mexican horde, as four White men, with fatalistic agency, casually saunter into their encampment, brutally gun down their commander and then giddily smile at their mestizo shock, is my favorite scene.

Ranking System:

0 Stars – Django Unchained

1 Stars – 100 Rifles

2 Stars – Bad Girls

3 Stars – The Burrowers

4 Stars – Tombstone

5 Stars – Once Upon a Time in the West

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History