Over the last decade, more than 2,700 US doctors and healthcare companies accused of wrongdoing collectively paid the US government $26.8 billion to negotiate their way out of trouble via civil settlements https://t.co/9RNwt08oGk by @MJBerens1 via @specialreports pic.twitter.com/AwZUMprHRK

— Reuters (@Reuters) May 24, 2023

‘Pay to stay’: A Michigan doctor accused of performing unnecessary radical hysterectomy procedures and administering excessive chemotherapy paid a $775,000 federal civil settlement and kept his license to practice. He admitted no wrongdoing https://t.co/D14pAaqrvh by @MJBerens1 pic.twitter.com/SCr7y46QjV

— Reuters (@Reuters) May 24, 2023

The veil was pulled back on the medical industrial complex during the coronavirus hoax, when doctors were literally killing people with poison injections and ventilators to get money from the government.

They were also just lying about “Covid” diagnoses, because the government was paying them to lie.

No one can possibly trust these rats at this point. It’s absurd.

Medical practitioners and providers paid $26.8 billion over the past decade to settle federal allegations including fraud, bribery and patient harm, a Reuters investigation found. Paying up means staying in business and, for some, avoiding prison. U.S. prosecutors helped them do it.

When federal enforcers alleged in 2015 that New York surgeon Feng Qin had performed scores of medically unnecessary cardiac procedures on elderly patients, they decided not to pursue a time-consuming criminal case.

Instead, prosecutors chose an easier, swifter legal strategy: a civil suit. Qin agreed to pay $150,000 in a negotiated settlement and walked free to perform more cardiac surgeries at his new solo practice in lower Manhattan.

Qin faced no judge or jury. He did not admit to wrongdoing. He maintained his license to practice. What’s more, neither Qin nor government officials were required to notify patients who purportedly were subjected to vascular surgical procedures they didn’t need. Those included fistulagrams to spot issues like narrowed blood vessels or clots, and angioplasties to open clogged coronary arteries.

Within months of the settlement, a registered nurse working for Qin at his Manhattan practice alerted authorities that something seemed amiss. The nurse, who ultimately turned whistleblower, alleged to federal prosecutors that the surgeon was performing unnecessary procedures on patients, mostly elderly Asian and Black immigrants whose care was covered by the public programs Medicare or Medicaid.

Based Chinaman milking the system?

Anyway, they’re giving you the Chinese example for obvious reasons. Most of the fraud is done by Jews and women. Also, probably a lot of white men. The medical profession is like the taxi driver profession – it simply attracts the most unscrupulous individuals of any race, because it is so easy, there is so much money, and it is so easy to commit fraud.

Prosecutors indicted Qin in 2018 on a felony count of fraud, which carried a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison. But in 2021, in a deal brokered behind closed doors, prosecutors dropped that charge in favor of yet another civil settlement, court records detailing that agreement show.

Once again, Qin kept his New York license to practice with no restrictions; a restricted license is one of the few ways the public can learn that a doctor has been disciplined for bad behavior. Qin agreed to pay a total of $800,000 in annual installments ending in December 2025, deposited with the U.S. Department of the Treasury. As an added penalty, he was banned from billing public health programs until February 2025.

Department of Justice officials and their investigative partner, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) for the Department of Health and Human Services, told Reuters that “conflicting evidence from experts” made it legally difficult to challenge Qin’s subjective surgical decisions, which led to the dropped indictment.

Federal agencies regulate billings and payments involving public health programs like Medicare. State governments, often working in tandem with a board of medical professionals, oversee licensing and disciplining of physicians and many other types of healthcare practitioners.

The New York Department of Public Health, which has authority over the New York State Medical board and speaks on its behalf, declined to comment on whether the state launched its own investigation of Qin.

Qin, in a response to this report through his attorneys, disputed the government’s allegations. But his settlement agreement included his signed acknowledgement that he had performed and billed for surgical procedures based on symptoms that were “insufficient to justify these treatments.”

The registered nurse who reported Qin to authorities in 2015 was stunned that the criminal charge was dropped.

“A wealthy doctor bought his way out of jail,” whistleblower Mark Favors told Reuters in his first public interview about the Qin case. “How many people get a deal like that?”

The answer, it turns out, is plenty.

Yes – many, many, many. But you chose the Chinaman as the example.

Over the last decade alone, at least 540 doctors and healthcare practitioners collectively paid the government hundreds of millions of dollars to negotiate their way out of trouble via civil settlements, then continued to practice medicine without restrictions on their licenses despite allegations that included fraud and patient harm, a Reuters investigation found. That figure is the result of the first-ever comprehensive analysis of federal civil settlements and state disciplinary actions.

Separately, more than 2,200 hospitals and healthcare companies likewise negotiated civil deals to sidestep prosecution for alleged offenses that included paying bribes, falsifying patients records and billing the government for unnecessary patient care, the Reuters analysis shows. In many of those cases, the physicians, staffers and top brass who purportedly committed those misdeeds were not named publicly by prosecutors or forced to pay settlements themselves. Federal enforcers said they sometimes withhold names of individuals in these situations because of ongoing or planned investigations.

It’s the exact same thing that goes on in the banking industry.

The reason it is so similar is that banking and medicine are run by the Jews.

The U.S. government collected more than $26.8 billion in healthcare-related civil settlements and judgments from 2013 to 2022, the Reuters analysis found.

In all, the news agency examined 2,788 federal civil settlement cases and administrative actions over that time period; that figure includes the 540 cases of doctors and other healthcare practitioners who kept their licenses after agreeing to civil deals. Most cases were jointly investigated by the Justice Department and the OIG of Health and Human Services.

Victims, meanwhile, received no share of these settlements, which are funneled to a Treasury Department general fund. Consequently, they must pursue their own civil cases in search of restitution for suffering and harm, Reuters found.

Yes.

Very typical: Jews get caught committing crimes and their punishment is to pay money to themselves.

Neither the government nor the alleged wrongdoers were required to notify patients who may have been affected. A recovering Michigan patient learned last year that her gynecologic oncologist had been accused of performing dozens of unnecessary surgeries – procedures like the one she underwent – only after seeing media reports about his settlement. A subsequent review of her medical records by another doctor revealed that her reproductive organs, which had been removed, were not cancerous, she told Reuters.

The U.S. civil justice system has become a key tactic in the government’s battle against healthcare fraud. Compared with criminal cases, civil settlements require a lower burden of proof and are generally quicker to litigate.

But the civil system also offers perks for suspected offenders, sometimes unintended, and often at the expense of patients, the Reuters analysis found.

In nearly every civil settlement agreement analyzed by Reuters, defendants were not required to acknowledge fault or liability. What’s more, about 9 in 10 businesses and individuals accused of falsely enriching themselves were allowed to continue billing the very government programs they had been accused of defrauding, Reuters found.

Tasked with protecting public health programs from waste and fraud, more than two dozen current and former federal prosecutors and investigators who spoke to Reuters defended settlements as a cost-effective compromise to recover taxpayer monies. They contend that compliance, not punishment, is the aim so that accused wrongdoers can stay in business, thus preserving public access to vital healthcare services.

Among the physicians who kept their licenses:

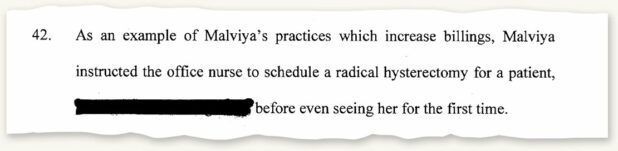

The Michigan doctor who treated the woman who said her reproductive organs were removed unnecessarily. He was accused of performing unwarranted radical hysterectomies and administering excessive chemotherapy treatments. Prosecutors allege the physician had already scheduled at least one patient for surgery before examining her for the first time. He paid $775,000 last year to settle.

A California doctor – the founder and owner of a national hospital chain – accused of a profit-driven scheme to hospitalize patients who required less costly, outpatient care. The doctor and his chain paid a combined $37.5 million last year to settle that case, which followed two similar settlements totaling $66.25 million.

Michigan and California medical board and health officials, who regulate healthcare licenses and impose disciplinary actions against offenders who violate state codes of conduct, told Reuters they were aware of the federal settlements in these respective cases. They declined to comment about whether they had received any complaints about these doctors or had initiated their own investigations.

Membership on nearly all state medical boards is dominated by doctors who make rules about conduct and decide punishment for their peers, according to Matthew Smith, executive director of the Washington-based Coalition Against Insurance Fraud. As a result, the system tends to protect physicians, he said.

“They look the other way. They don’t want to know,” said Smith, whose organization advocates anti-fraud laws on behalf of insurers and a consortium of government agencies, law enforcement and consumer groups.

Some state medical boards have policies that seemingly thwart or discourage complaints of wrongdoing, Smith said. These include requiring parties making complaints to do so in notarized statements, and disclosing their identities to accused doctors, according to data from the Federation of State Medical Boards, a Washington-based nonprofit trade organization.

Secrecy is also pervasive, federation data shows. In at least 28 states, boards can issue confidential disciplinary orders to close cases without public disclosure; not even the complainant is allowed to know what happened.

The issue is: the problem is systemic. It’s not about individual doctors or hospitals. The entire medical complex was designed for fraud.

Doctors are effectively a criminal gang, like the bankers or the cops.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History