Bill Gates is a legit super-villain, and unlike the people in Western intelligence, he’s actually relatively competent.

The Wall Street Journal has a piece up this week laying out his master plan to turn the earth into a frozen wasteland.

The quickies:

- Bill Gates calls Anthony Fauci “Tony Fauci,” and says “Tony Fauci and I were quite obscure and would go to cocktail parties and nobody would talk to us.”

- Bill Gates is a superhero on a quest to save the planet from mass extinction

- Bill Gates is a nuclear plant expert

- Bill Gates is a climate change expert

- Bill Gates is a coronavirus expert

- Bill Gates is a vaccination expert

- Bill Gates is an all-things expert and your new daddy

Now, for those who want to go beyond the quickies, let’s see the thingies.

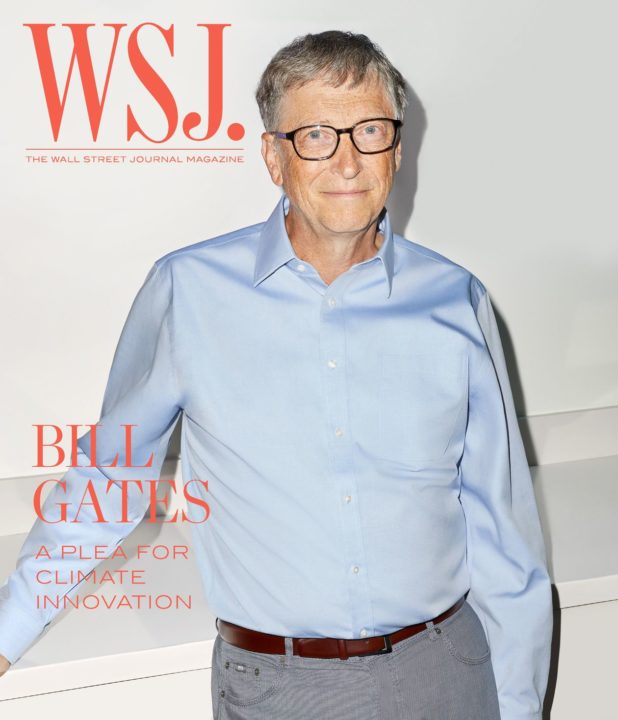

The co-founder of Microsoft became obsessed with developing clean tech through his philanthropic work. With a new book, ‘How to Avoid a Climate Disaster,’ and a cadre of billionaire partners, he now has an action plan for ending the world’s carbon dependency.

A day before the inauguration, as Lady Gaga rehearsed “The Star-Spangled Banner” in Washington, D.C., wildfires burned in Sonoma, Santa Cruz and Ventura counties in California, shocking climatologists who had never witnessed the state’s fire season extend into January. NASA had just announced that 2020 tied with 2016 for the warmest year on record. As the Covid-19 pandemic drove city dwellers to search for places that felt surer, safer—Vermont, Kansas, Idaho—the FBI began arresting Americans who had rioted in the U.S. Capitol. Online sales of “prepper” gear (gas masks, food preservation kits) were brisk.

Bill Gates was at his lakeside compound in Seattle, gearing up for his next effort to save the planet from mass extinction. For 20 years, Gates has been studying the twin global afflictions of disease and poverty. These efforts led him to consider climate change and its vexing impact on civilization. This month, Knopf will publish his latest book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster. Remarkably, given the state of the world, it is an optimistic, can-do sort of book, chock-full of solutions for a problem President Jimmy Carter began warning about in 1977.

Last month’s inauguration of President Joe Biden had a big influence on Gates’s outlook. An earlier draft of the book included measures for a second Donald Trump term. In November, after the election, he edited these parts out, including provisions for how U.S. state and foreign governments could account for an absence of federal support. Another Trump win, Gates says, would have left us “holding our breath for four years and trying not to turn blue.”

“I hope Joe Biden stays healthy,” he had told me during our first virtual interview in December, while seated in a glass-walled conference room at Gates Ventures known as the fishbowl, where he has been taking meetings and relying on the Microsoft Teams platform during the pandemic.

…

Although he has confidence in our collective ability to avoid the earth’s descent into a landscape of scorched rainforests and liquefying glaciers, his prescription is daunting: The planet must reduce the amount of greenhouse emissions being pumped into the atmosphere, currently about 51 billion tons per year, to zero by 2050. Nothing less, he says, will prevent a catastrophe, and he is calling for a full-scale technological revolution to make it happen.

…

The crux of his argument is that, as helpful as innovations like electric cars, solar panels, lithium-ion batteries and plant-based burgers are to the effort, they don’t go far enough. There isn’t enough land on earth to plant enough trees to offset our carbon dependency. “The key point in my book is that a serious climate plan—which we don’t have yet—involves counting in your head all the different sources of emissions,” Gates says. This reckoning has to go beyond agriculture and electricity to encompass all carbon-spewing processes (transportation; concrete and steel production) so that we can develop green alternatives. So, for example, Gates believes we must invent green steel.

…

Gates gave a TED Talk about climate change in 2010. It hasn’t received as much attention as his pandemic-warning talk, but it marks the point when he grasped that greenhouse gases were hampering the philanthropic goals of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In the early naughts, he was traveling frequently to sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia to study child mortality, HIV and other problems. Traveling in Lagos, Nigeria, one night, he recounts in his book, he wondered at the city’s relative darkness and many unlit homes. Gates recognized a form of impoverishment that he hadn’t considered—energy poverty.

Note: he’s been planning this for a long time.

By 2006, the year An Inconvenient Truth, Al Gore’s groundbreaking documentary about global warming, came out, Gates had invested in energy development. So-called clean tech had become trendy, with more than $25 billion pouring into solar power, battery companies and other new technologies from 2006 to 2011. Gates went all in, even investing in nuclear energy, which, unlike solar and wind, provides a constant, not intermittent, power source.

Clean-tech venture markets crashed in 2011. Fracking had cut the cost of natural gas, depressing demand for green alternatives. One heavily hyped solar-panel startup, Solyndra, illustrates the complexity of funding energy innovation. Solyndra’s thin-film solar cells, a promising technology subsidized with $535 million in federal loan guarantees, proved too expensive to compete with government-subsidized imports from China. The company went bankrupt in 2011, leaving taxpayers ultimately on the hook for the loan.

An analysis by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology estimates that venture investors lost more than half of their money on Cleantech 1.0. Gates is unfazed by such losses. He says he has personally invested $2 billion in climate change innovation so far and expects to invest another $2 billion over the next five years. “I’m only going to lose money on this stuff,” he says, shrugging. “But that’s not in short supply.”

Note: just like Hollywood movies are not about profit, Bill Gate’s investments are not about profit. Also like Hollywood movies, his investments are not a charity to improve people’s lives but a malicious attempt at transforming the world into something wicked.

Gates’s current thinking about climate innovation galvanized in June 2015. While attending meetings in London, he was probed by an editor at the Financial Times about the lack of pioneering research into clean-energy solutions. The exchange bugged him. During a meeting the next afternoon in a suite at the Four Seasons Hotel on Park Lane, he began pacing and mumbling, according to two people who were with him at the time, Larry Cohen, head of Gates’s private office, Gates Ventures, and Jonah Goldman, who runs Gates’s policy and advocacy, including climate efforts. “It’s just not enough of a focus, and the wrong people are organizing this,” Gates muttered.

As his group left the hotel and climbed into a black Mercedes van to head to another meeting, Gates and his team concocted a plan to vastly increase the amount of public and private money going toward energy innovation. By the time he emerged on the other side of London, Gates had decided to create a venture capital fund and to organize government leaders to invest billions of dollars in climate technology. “We could call it Breakthrough Energy,” Gates later posited.

“That was not what we expected when we landed in London,” says Goldman.

The speed of what followed reflects the magnitude of Gates’s reach. He pitched then–French president François Hollande the next day in Paris at the Élysée Palace. In September, he crashed a United Nations meeting between Hollande and India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, to pitch the leader of one of the world’s biggest carbon producers. Modi, enthusiastic about the idea, proposed his own name for the coalition, Mission Innovation, which Gates accepted.

In Seattle, Gates’s team began to structure the $1 billion venture fund. When Gates laid out the plan to Rodi Guidero, managing director for strategic investments at Gates Ventures (who now oversees Breakthrough Energy Ventures), Guidero blurted, “That’s a terrible f—ing idea.” He argued the fund would lose money and embarrass Gates.

“Why do you think I care about that?” Gates replied.

…

In the fall of 2015, Gates emailed a global cadre of billionaires who could afford to lose tens of millions investing in Breakthrough Energy Ventures. They included Jack Ma, Jeff Bezos, Vinod Khosla and Prince al-Waleed bin Talal.

It turned out to be an appealing club to join, and a model of global billionaire diversity (although female members are scarce). Other investors include Michael Bloomberg, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son, South African mining businessman Patrice Motsepe, Mukesh Ambani (India’s wealthiest person), Richard Branson, Bridgewater hedge-fund founder Ray Dalio and Beijing real-estate developers Zhang Xin and Pan Shiyi.

Yeah, he for sure needs more women involved.

Women really help with productivity.

The only reason every company doesn’t hire a majority women is that they hate the shape of the genitals.

John Doerr, the legendary venture capitalist at Kleiner Perkins who made early bets on Netscape, Amazon and Google, says the $50 million he put into the venture was his biggest-ever personal investment at the time. “The idea that we would gather entrepreneurs and business leaders from around the globe…I found exciting,” Doerr says. “I think it’s one of the most remarkable pieces of fundraising I’ve ever witnessed.”

Doerr is a believer. He says the climate crisis is the next big investment opportunity. “This is the mother of all markets,” he says.

“It was stunning to me how easy it was to raise the money,” Gates says.

…

Gates is particularly fond of TerraPower, a Bellevue, Washington–based developer of safer nuclear energy that Gates co-founded in 2008, with an investment that reports estimated at the time as more than $500 million. Gates, who declined to confirm the size of his initial investment, does not share most of the world’s terror of nuclear technology.

“Nobody’s gone back and done a complete redesign of a nuclear energy plant since those early days of the ’50s,” Gates says. “So the question is, in the digital age, can you build a nuclear reactor whose economics, safety potential and waste output are utterly different than the current generation of nuclear? You really have to start from scratch.”

Note: current nuclear power plants work fine, they just don’t want to use them as it’s just too obvious of a solution to the whole carbon gibberish, which is about control.

TerraPower’s approach, designed after Gates paid for supercomputer modeling, stores heat in tanks of molten salt. Without high pressure, the technology will eventually be able to run on spent fuel rods, so that existing stockpiles of nuclear waste are reduced as they are recycled.

“Can nuclear be super safe?” Gates asks. “I say yes.”

…

It isn’t helpful to interrupt Bill Gates. He speaks in circles, wending his way around ideas and unleashing a cascade of details that can be difficult to follow until its conclusion. “I’m not a natural like Steve Jobs, who could really get people riled up,” he says.

When I asked what makes him good at solving complex problems, Gates spoke without hesitation for six minutes and 45 seconds, touching on his approach to eradicating malaria, building strong teams, his understanding of concrete and cement, Americans’ generally more positive outlook about nuclear energy than the Europeans’, and much more. He concluded, “This is fun work.”

He paces, according to colleagues, and his voice gets squeaky when he’s excited, but he often fails to emote when faced with tragedy. “It’s actually hard to convey what it’s like to be there watching a kid who’s dying of malaria. I could get better at that,” he says. In a social setting, small talk is not his thing. Gates is the guy in the corner talking to another brainiac.

“Tony Fauci and I were quite obscure and would go to cocktail parties and nobody would talk to us,” says Gates of the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who has taken a star turn during Covid-19. “Now Tony’s like the rock star and Saturday Night Live has women throwing bras at him.”

Note: Bill Gates may be driven by a need to “undo” his past status as a pariah; he’s totally deranged.

Melinda Gates, whom Gates married in 1994, is often seen as a humanizing influence on her husband, a scenario neither of them appears to relish. (Through spokespeople she declined to be interviewed for this piece.) The couple has three children, Jennifer, a 24-year-old medical student; Rory, 21, and Phoebe, 18, both college students.

Melinda does offer social guidance, Gates acknowledges. She counseled against making too many references to cow farts, he writes in How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, attempting to limit his mentions of the methane produced by ruminant livestock.

Yet he thinks the popular view of Melinda as his alter ego is shortsighted. “Melinda and I are more alike than people think,” Gates says. “Yes, you can see her empathy more easily than mine—though I cry more easily than she does. Melinda’s very analytical—like top-1-percent analytical, though yes, I’m weirdly even more analytical.”

But she sure does love the blacks.

It makes a lot of sense that the incompetent US government is surrendering total control over to this man and his ilk.

He certainly has a clear vision, and a plan to enact that vision. That’s a lot more than we can say about the unhinged sadists in the US government.

Related: As Institutionalized Incompetence Grows, Biden is a Figure for the Transition Into a New World Order

Thus far, as we’ve seen across the planet, the Joe Biden executive orders drawn up by Gates to change the weather have been working very well.

The whole place is an ice storm.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History