Imagine how far the government and the military are likely to have taken this kind of research.

A study that’s sure to put readers in a trance finds hypnosis actually changes how our brains work. Hypnosis has been depicted time and time again in movies and other forms of popular culture. The recent hit “Get Out” immediately comes to mind, or perhaps Jafar’s hypnotic snake scepter in “Aladdin” from 1992. Beyond the value of hypnosis as a plot device however, its actual influence on the brain has been unclear. Now, researchers from the University of Turku say they have evidence the human brain processes information differently under hypnosis.

During normal consciousness, various regions of the human brain work together and collaborate to help us process, understand, and react to external stimuli. While hypnotized, the brain seems to “shift gears” toward a more singular approach. In other words, when someone is in a trance, individual brain regions act independently.

“In a normal waking state, different brain regions share information with each other, but during hypnosis this process is kind of fractured and the various brain regions are no longer similarly synchronized,” says researcher Henry Railo from the Department of Clinical Neurophysiology in a university release.

…

This study focused on a single individual who had already been studied extensively regarding hypnosis. The participant displayed a strong susceptibility to hypnotic suggestions. In particular, they can even experience hallucinations while under trance and all it takes is a single word to induce a hypnotic state.

“Even though these findings cannot be generalized before a replication has been conducted on a larger sample of participants, we have demonstrated what kind of changes happen in the neural activity of a person who reacts to hypnosis particularly strongly,” clarifies Jarno Tuominen, Senior Researcher at the Department of Psychology and Speech-Language Pathology.

Researchers tracked a magnetically-induced electrical current as it spread throughout the individual’s brain during both hypnosis and a normal waking state. This is the first time such an approach has been used to assess hypnotic consciousness versus being awake. In the past the same technique has measured brain changes between sleep, coma, and anesthesia.

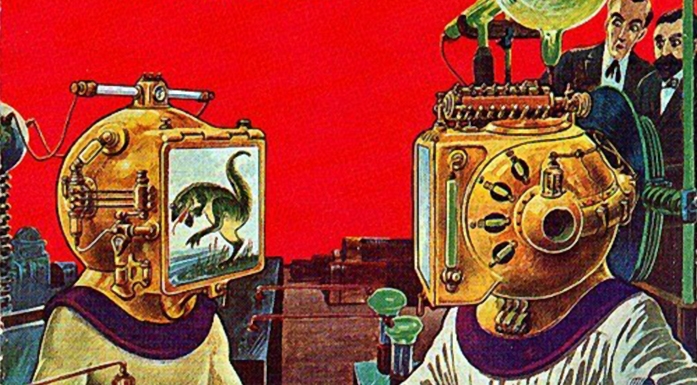

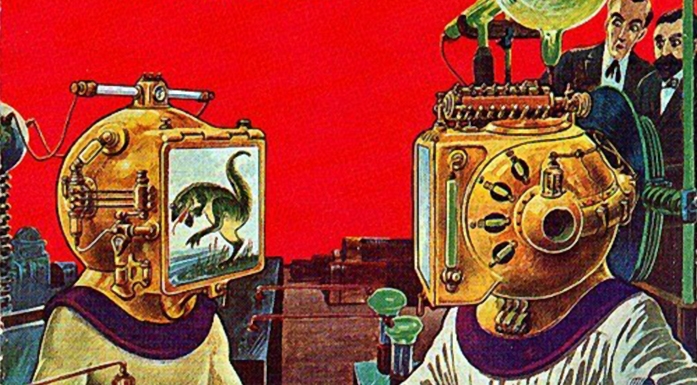

It is probably possible to use electromagnetic waves to induce the hypnotic state in people not naturally susceptible to hypnosis. They could also use images on a computer screen to program your thoughts, presumably.

There are all kinds of “fun” research projects that the rulers could be conducting on the goyim’s brains behind the scenes.