When Kamala Harris told this weird story about Abraham Lincoln during the debate, even I said, “surely, there must be some truth to it.”

But it turns out there actually isn’t.

When you start getting called out by the WaPo for liberal hoaxes, you’re in a real bad way.

“There have been 29 vacancies on the Supreme Court during presidential election years from George Washington to Barack Obama, and the presidents have nominated in all 29 cases,” Pence said, failing to mention his party refused to vote on Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland. “But your party is actually openly advocating adding seats to the Supreme Court, which has had nine seats for 150 years, if you don’t get your way.”

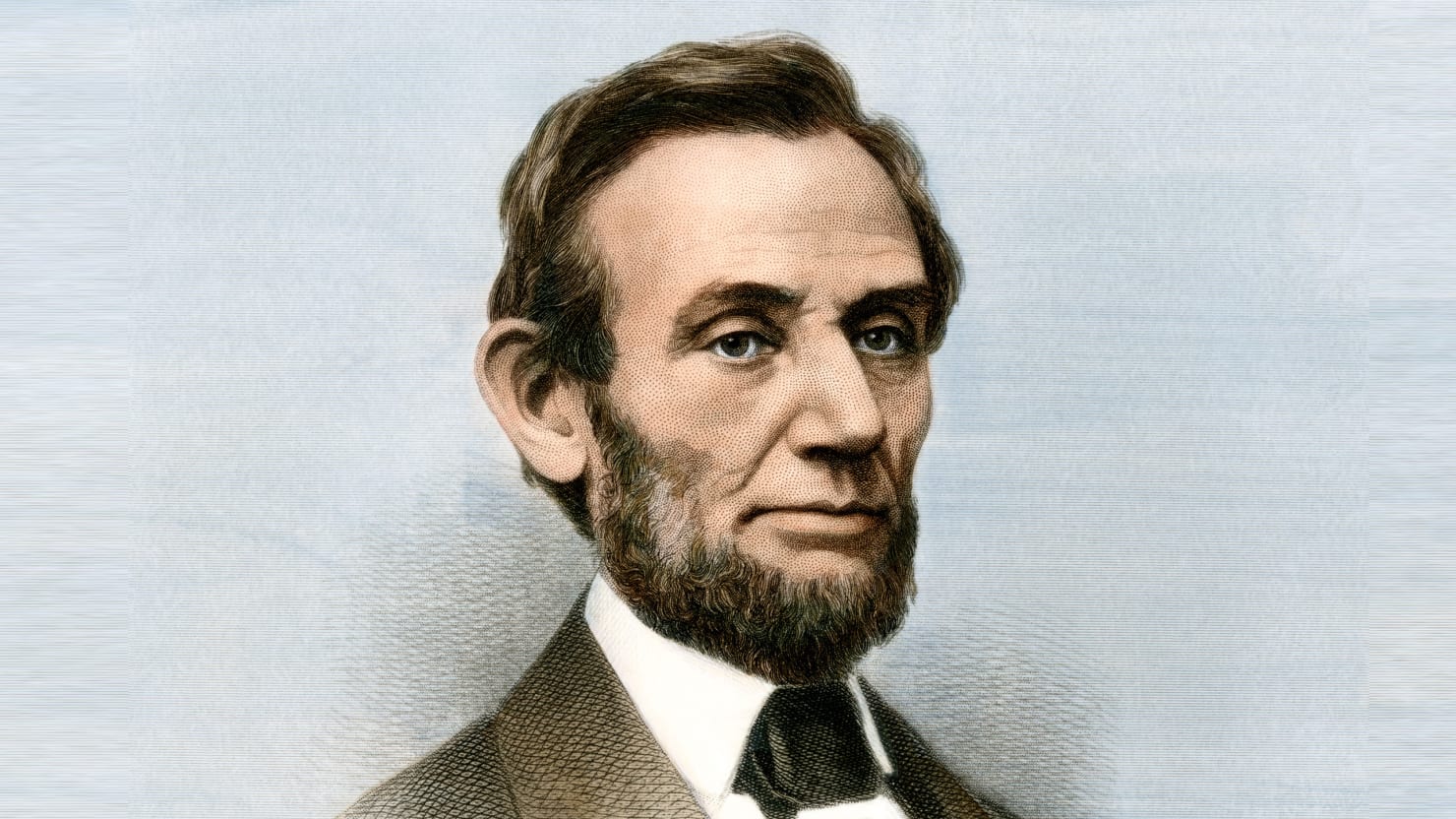

“I’m so glad we went through a little history lesson. Let’s do that a little more,” Harris responded. “In 1864 … Abraham Lincoln was up for reelection. And it was 27 days before the election. And a seat became open on the United States Supreme Court. Abraham Lincoln’s party was in charge not only of the White House but the Senate. But Honest Abe said, ‘It’s not the right thing to do. The American people deserve to make the decision about who will be the next president of the United States, and then that person will be able to select who will serve on the highest court of the land.’”

So, is that true?

Harris is correct that a seat became available 27 days before the election. And that Lincoln didn’t nominate anyone until after he won. But there is no evidence he thought the seat should be filled by the winner of the election. In fact, he had other motives for the delay.

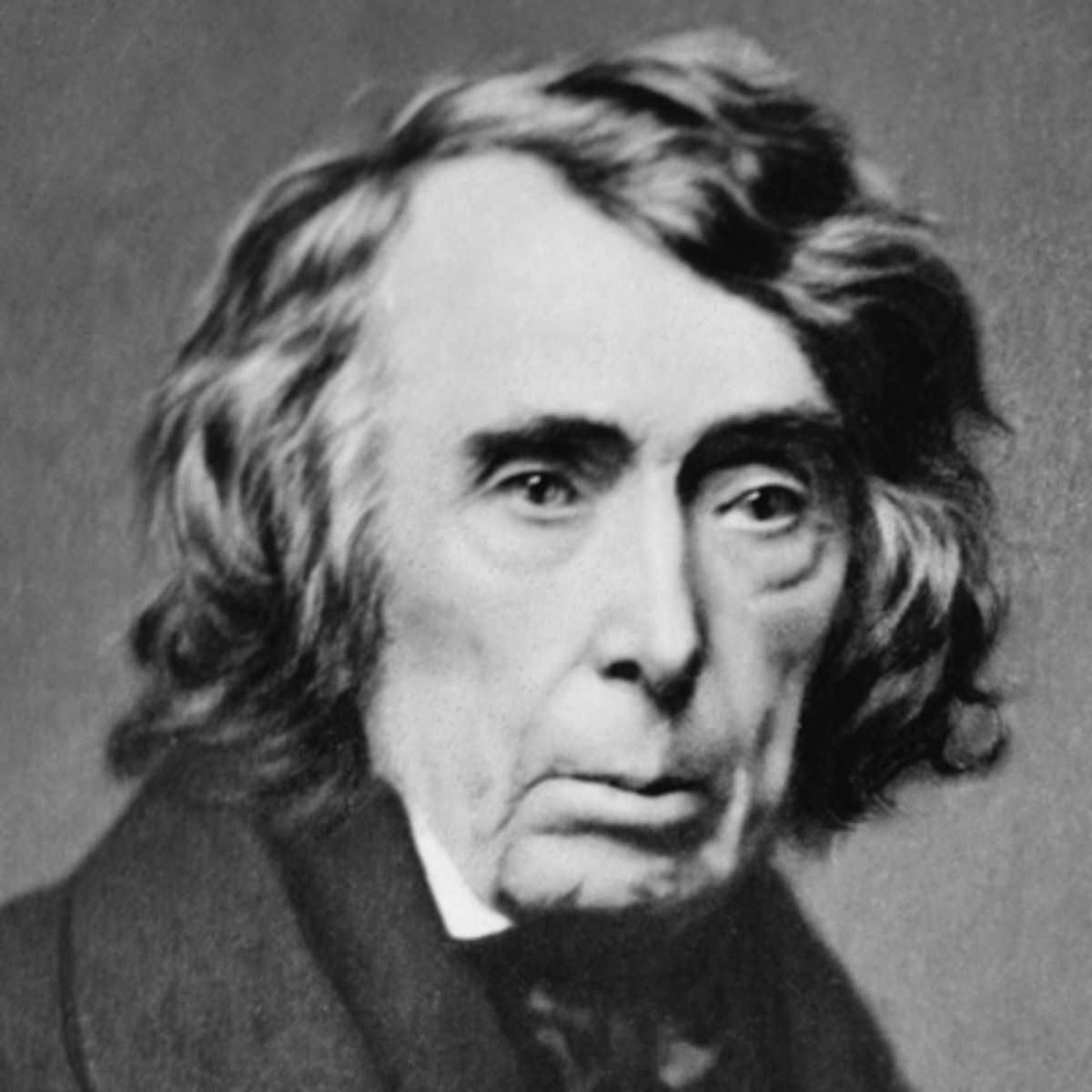

On Oct. 12, 1864, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney died at the age of 87. He had been chief justice for nearly 30 years but will always be best-known — or rather, notorious — for writing the majority opinion in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case, in which he declared that Black people were inferior and “had no rights which the White man was bound to respect.” (The House voted to remove a bust of Taney from the U.S. Capitol over the summer amid the George Floyd protests.)

Taney had been sick for years, so it didn’t come as a surprise to Lincoln that he might have the opportunity to name his own chief justice, according to Michael Kahn, the former head of the board of directors of President Lincoln’s Cottage. But Lincoln was preoccupied with both his campaign and the Civil War — Sherman’s troops had just captured Atlanta and would soon march to the sea. He told his aides he wouldn’t nominate anyone immediately, because he was “waiting to receive expressions of public opinion from the country,” according to historian Michael Burlingame in “Lincoln: A Life.”

But that didn’t mean he was waiting for ballots so much as the mail. Letters flooded in from all over the country. What about Secretary of War Edwin Stanton? some suggested. Or Associate Justice Noah Swayne? Francis P. Blair recommended his son Montgomery, the postmaster general. Attorney General Edward Bates recommended himself.

And then there was Salmon P. Chase. Chase was a former senator, governor of Ohio and treasury secretary who, according to Burlingame, thought he was destined to be president. He had vied unsuccessfully against Lincoln for the Republican nomination in 1860. Though Lincoln disliked him, Chase had a lot of supporters. Chase’s opponents told Lincoln all the nasty things Chase had said about him behind his back.

The overarching effect of the delay is that it held Lincoln’s broad but shaky coalition of conservative and radical Republicans together. And it kept rivals like Chase in line. Chase, who had often been critical of Lincoln in the past, immediately began stumping for the president across the Midwest, sparking rumors of a secret deal, according to Kahn.

Congress was in recess until early December, so there would have been no point in naming a man before the election anyway. Lincoln shrewdly used that to his advantage. If he had lost the election, there is no evidence he wouldn’t have filled the spot in the lame-duck session.

Lincoln was, of course, reelected. And the day after the Senate was back in session, he nominated Chase for chief justice. He hoped the august appointment would “neutralize” Chase’s designs on the presidency. (It didn’t.)

So Harris is mistaken about Lincoln’s motivations in this regard.

Harris obviously knew this story she told was a lie.

Or rather, the people who wrote her lines for the debate knew it was a lie.

They probably didn’t expect the WaPo to call them out on it, but even so, most people will not read this article.

What an evil bitch.

It was so sick how she sent that fly at Pence that way.

Truly beyond the pale.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History