What we’re seeing now is all of the Edward Snowden and Julian Assange stuff about domestic spying coming into the forefront and being normalized.

We here at Daily Stormer – which was known at the time as Hoax Watch – were very vocal about the FBI saying publicly that they were buying cellphone GPS data from “private companies” and using it to track the January 6 patriots.

That is not exactly the same thing as NSA/CIA spying, but it’s what you would be talking about if you were doing a thing where you were trying to normalize illegal domestic spying. Because the NSA was cooperating with Google and Microsoft and Apple and everyone else to install backdoors on devices and programs so they could bulk collect everyone’s data.

Recently, they’ve run with this libertarian narrative of “private companies can do anything to anyone” with regards to censorship. Now, we’ve found out that the government was telling these companies what to censor, but if you follow this hardline libertarian ideology being pushed by the socialists, the companies can choose to cooperate with the government, because private companies can do whatever they want.

Censorship and domestic spying are both pretty interlinked “ethical dilemmas” of the digital age, so these narratives are going to crisscross with one another. The government is cooperating on both, using the same libertarian ideological principles.

Libertarianism has always been communism with extra steps.

This is a long article, but we’re going to quote from it at length – as always, you can read it or not (a lot of people say they just read our commentary and then skim the articles – you’ll get the general idea).

But this is important information, so it is worth quoting at length. This is the emergence of a total control grid.

AP:

Local law enforcement agencies from suburban Southern California to rural North Carolina have been using an obscure cellphone tracking tool, at times without search warrants, that gives them the power to follow people’s movements months back in time, according to public records and internal emails obtained by The Associated Press.

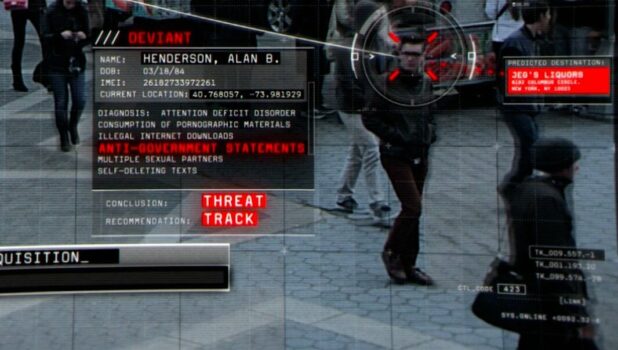

Police have used “Fog Reveal” to search hundreds of billions of records from 250 million mobile devices, and harnessed the data to create location analyses known among law enforcement as “patterns of life,” according to thousands of pages of records about the company.

Sold by Virginia-based Fog Data Science LLC, Fog Reveal has been used since at least 2018 in criminal investigations ranging from the murder of a nurse in Arkansas to tracing the movements of a potential participant in the Jan. 6 insurrection at the Capitol. The tool is rarely, if ever, mentioned in court records, something that defense attorneys say makes it harder for them to properly defend their clients in cases in which the technology was used.

The company was developed by two former high-ranking Department of Homeland Security officials under former President George W. Bush. It relies on advertising identification numbers, which Fog officials say are culled from popular cellphone apps such as Waze, Starbucks and hundreds of others that target ads based on a person’s movements and interests, according to police emails. That information is then sold to companies like Fog.

“It’s sort of a mass surveillance program on a budget,” said Bennett Cyphers, a special adviser at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital privacy rights advocacy group.

By the way, EFF is run by Jews.

Andrew Anglin contacted that Jew woman who runs it when we were on the ropes in 2017, and she was like “oh sorry, there’s nothing I can do, goy.” She did say “yes we’re against this” and Anglin was like “well, I’m pretty sure you’re supposed to give me money for a lawsuit – no one has ever been censored like this in all of history.” She was just like “oh, yes, we will look into it, but there is nothing we can do.” Then it was like “so what is the purpose of your organization?” and she was like “we’ll get back to you.”

We’re still waiting.

This story, supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, is part of an ongoing Associated Press series, “Tracked,” that investigates the power and consequences of decisions driven by algorithms on people’s everyday lives.

The documents and emails were obtained by EFF through Freedom of Information Act requests. The group shared the files with The AP, which independently found that Fog sold its software in about 40 contracts to nearly two dozen agencies, according to GovSpend, a company that keeps tabs on government spending. The records and AP’s reporting provide the first public account of the extensive use of Fog Reveal by local police, according to analysts and legal experts who scrutinize such technologies.

Federal oversight of companies like Fog is an evolving legal landscape. On Monday, the Federal Trade Commission sued a data broker called Kochava that, like Fog, provides its clients with advertising IDs that authorities say can easily be used to find where a mobile device user lives, which violates rules the commission enforces. And there are bills before Congress now that, if passed, would regulate the industry.

“Local law enforcement is at the front lines of trafficking and missing persons cases, yet these departments are often behind in technology adoption,” Matthew Broderick, a Fog managing partner, said in an email. “We fill a gap for underfunded and understaffed departments.”

Because of the secrecy surrounding Fog, however, there are scant details about its use and most law enforcement agencies won’t discuss it, raising concerns among privacy advocates that it violates the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protects against unreasonable search and seizure.

What distinguishes Fog Reveal from other cellphone location technologies used by police is that it follows the devices through their advertising IDs, unique numbers assigned to each device. These numbers do not contain the name of the phone’s user, but can be traced to homes and workplaces to help police establish pattern-of-life analyses.

“The capability that it had for bringing up just anybody in an area whether they were in public or at home seemed to me to be a very clear violation of the Fourth Amendment,” said Davin Hall, a former crime data analysis supervisor for the Greensboro, North Carolina, Police Department. “I just feel angry and betrayed and lied to.”

Hall resigned in late 2020 after months of voicing concerns about the department’s use of Fog to police attorneys and the city council.

While Greensboro officials acknowledged Fog’s use and initially defended it, the police department said it allowed its subscription to expire earlier this year because it didn’t “independently benefit investigations.”

But federal, state and local police agencies around the U.S. continue to use Fog with very little public accountability. Local police agencies have been enticed by Fog’s affordable price: It can start as low as $7,500 a year. And some departments that license it have shared access with other nearby law enforcement agencies, the emails show.

Police departments also like how quickly they can access detailed location information from Fog. Geofence warrants, which tap into GPS and other sources to track a device, are accessed by obtaining such data from companies, like Google or Apple. This requires police to obtain a warrant and ask the tech companies for the specific data they want, which can take days or weeks.

Using Fog’s data, which the company claims is anonymized, police can geofence an area or search by a specific device’s ad ID numbers, according to a user agreement obtained by AP. But, Fog maintains that “we have no way of linking signals back to a specific device or owner,” according to a sales representative who emailed the California Highway Patrol in 2018, after a lieutenant asked whether the tool could be legally used.

Despite such privacy assurances, the records show that law enforcement can use Fog’s data as a clue to find identifying information. “There is no (personal information) linked to the (ad ID),” wrote a Missouri official about Fog in 2019. “But if we are good at what we do, we should be able to figure out the owner.”

Fog’s Broderick said in an email that the company does not have access to people’s personal information, and draws from “commercially available data without restrictions to use,” from data brokers “that legitimately purchase data from apps in accordance with their legal agreements.” The company refused to share information about how many police agencies it works with.

“We are confident Law Enforcement has the responsible leadership, constraints, and political guidance at the municipal, state, and federal level to ensure that any law enforcement tool and method is appropriately used in accordance with the laws in their respective jurisdictions,” Broderick said in the email.

“Search warrants are not required for the use of the public data,” he added Thursday, saying that the data his product offers law enforcement is “lead data” and should not be used to establish probable cause.

Kevin Metcalf, a prosecutor in Washington County, Arkansas, said he has used Fog Reveal without a warrant, especially in “exigent circumstances.” In these cases, the law provides a warrant exemption when a crime-in-process endangers people or an officer.

Metcalf also leads the National Child Protection Task Force, a nonprofit that combats child exploitation and trafficking. Fog is listed on its website as a task force sponsor and a company executive chairs the nonprofit’s board. Metcalf said Fog has been invaluable to cracking missing children cases and homicides.

“We push the limits, but we do them in a way that we target the bad guys,” he said. “Time is of the essence in those situations. We can’t wait on the traditional search warrant route.”

…

Fog has aggressively marketed its tool to police, even beta testing it with law enforcement, records show. The Dallas Police Department bought a Fog license in February after getting a free trial and “seeing a demonstration and hearing of success stories from the company,” Senior Cpl. Melinda Gutierrez, a department spokeswoman, said in an email.

Fog’s tool is accessed through a web portal. Investigators can enter a crime scene’s coordinates into the database, which brings back search results showing a device’s Fog ID, which is based on its unique ad ID number.

Police can see which device IDs were found near the location of the crime. Detectives or other officers can also search the location for IDs going forward from the time of the crime and back at least 180 days, according to the company’s user license agreement.

The emails and Fog’s Broderick contend the tool can actually search back years, however. Emails from a Fog representative to Florida and California law enforcement agencies said the tool’s data stretched back as far as June 2017. On Thursday Broderick, who had previously refused to address the question, said it “only has a three year reach back.”

While the data does not directly identify who owns a device, the company often gives law enforcement information it needs to connect it to addresses and other clues that help detectives figure out people’s identities, according to company representatives’ emails.

It is unclear how Fog makes these connections, but a company it refers to as its “data partner” called Venntel, Inc. has access to an even greater trove of users’ mobile data.

…

Fog Data Science LLC is headquartered in a nondescript brick building in Leesburg, Virginia. It also has related entities in New Jersey, Ohio and Texas.

It was founded in 2016 by Robert Liscouski, who led the Department of Homeland Security’s National Cyber Security Division in the George W. Bush adminstration. His colleague, Broderick, is a former U.S. Marine brigadier general who ran DHS’ tech hub, the Homeland Security Operations Center, during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. A House bipartisan committee report cited Broderick among others for failing to coordinate a swift federal response to the deadly hurricane. Broderick resigned from DHS shortly thereafter.

In marketing materials, Fog also has touted its ability to offer police “predictive analytics,” a buzzword often used to describe high-tech policing tools that purport to predict crime hotspots. Liscouski and another Fog official have worked at companies focused on predictive analytics, machine learning and software platforms supporting artificial intelligence.

“It is capable of delivering both forensic and predictive analytics and near real-time insights on the daily movements of the people identified with those mobile devices,” reads an email announcing a Fog training last year for members of the National Fusion Center Association, which represents a network of intelligence-sharing partnerships created after the Sept. 11 attacks.

Fog’s Broderick said the company had not invested in predictive applications, and provided no details about any uses the tool had for predicting crime.

Despite privacy advocates’ concerns about warrantless surveillance, Fog Reveal has caught on with local and state police forces. It’s been used in a number of high-profile criminal cases, including one that was the subject of the television program “48 Hours.”

In 2017, a world-renowned exotic snake breeder was found dead, lying in a pool of blood in his reptile breeding facility in rural Missouri. Police initially thought the breeder, Ben Renick, might have died from a poisonous snake bite. But the evidence soon pointed to murder.

During its investigation, emails show the Missouri State Highway Patrol used Fog’s portal to search for cellphones at Renick’s home and breeding facility and zeroed in on a mobile device. Working with Fog, investigators used the data to identify the phone owner’s identity: it was the Renicks’ babysitter.

Police were able to log the babysitter’s whereabouts over time to create a pattern of life analysis.

It turned out to be a dead-end lead. Renick’s wife, Lynlee, later was charged and convicted of the murder.

Prosecutors did not cite Fog in a list of other tools they used in the investigation, according to trial exhibits examined by the AP.

But Missouri officials seemed pleased with Fog’s capabilities, even though it didn’t directly lead to an arrest. “It was interesting to see that the system did pick up a device that was absolutely in the area that day. Too bad it did not belong to a suspect!” a Missouri State Highway Patrol analyst wrote in an email to Fog.

In another high-profile criminal probe, records show the FBI asked state intelligence officials in Iowa for help with Fog as it investigated potential participants in the events at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6.

As you may have noticed, there are also implications here about an emerging federalization of local law enforcement, as they are all becoming interlinked through computer systems which use third party “private companies” as relay points.

It’s a Matrix type technological control grid that the establishment is building. Whether an organization is a part of the government or a part of the private sector is totally irrelevant, aside from the way it is organized within the establishment structure.

The people who work for the government are constantly going in and out of these private companies, and the government does all kinds of contracting on all different levels, and with most of these spying companies, they’re run by “former” intelligence officials who, one would think, are still working for the intelligence agencies and simply “retire” (often in their 40s) to start these companies as part of a government network.

Hopefully, Glenn Greenwald will do some of the legwork on this soon. The recent revelations about the government communicating with social media on censorship were totally narrative breaking.

Remember when they were telling us that “it’s not the government”? It turns out it actually was the government the whole time.

But as I say, they are now saying that private companies are allowed to work with the government. So the government isn’t allowed to censor you or spy on you, but they are allowed to tell a private company to do that, and pay them to do it through awarding contracts or buying data.

It’s all so ridiculously Jewish, it will make your head spin.

There you go. Finally, a good piece of journalism. Bravo.

— known (@BaezBaezrogelio) September 4, 2022

Yeah. Noone has ever had charges drummed up on them.

— Jeremy Crockett (@jcrock1711) September 4, 2022

The surveillance state is slowly revealing itself. The data should be shared with Defense attorneys under Brady. According to SCOTUS they don’t have as of this year. 🤦🏾♀️🤦🏾♀️

— Elva Carter No DM’s please (@CarterElva) September 4, 2022

Privacy is an illusion, regrettably. Beyond that, at minimum, law enforcement should follow the laws that they are constitutionally required to enforce.

— Olivia P. Walker (@olivia_p_walker) September 4, 2022

WTH?

— Grey Fox (@yesitismine) September 4, 2022

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History