This week, Vanity Fair published an 8,000-word hit piece entitled “The Secret History of Gavin McInnes.” The fake news journalist, Adam Leith Gollner, tells people the origin story of the ancient evil Nazi mastermind and full-time career comic book villain currently known as “Gavin McInnes.”

McInnes is to modern day America what Osama bin Laden was to 2001-era America.

This is the story of how a man became Ultimate Evil.

Psychoanalysis is key to understanding the psycho-sexual motivations of pure evil.

On election night in 2016, four years before the January 6 storming of the U.S. Capitol, the proud boys threw a party. That November evening, Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes—my former boss—summoned his followers to the Gaslight Lounge in New York’s Meatpacking District to watch the returns. “Tonight we either take back the country or we lose the country to the establishment,” he told the attendees, a mixture of Trumpist trolls, frat bros, and the sort of amped-up nationalist types who call themselves “Western chauvinists.”

McInnes had just created his gang months before. But as someone who’d always predicted trends, he could see where this would lead. “If Donnie wins,” he bellowed into a distorting microphone, the Proud Boys will “own America. We’ll just walk into the White House.” They began chanting “USA! USA! USA!” the same way the Proud Boys would when breaching the Capitol complex in January. Few back in 2016 realized how far the group would go—soon establishing chapters in 45 states, with members eventually indicted on charges ranging from civil disorder to conspiracy in the Washington, D.C., rampage. McInnes had founded what would become, according to the Canadian government, a “terrorist entity.”

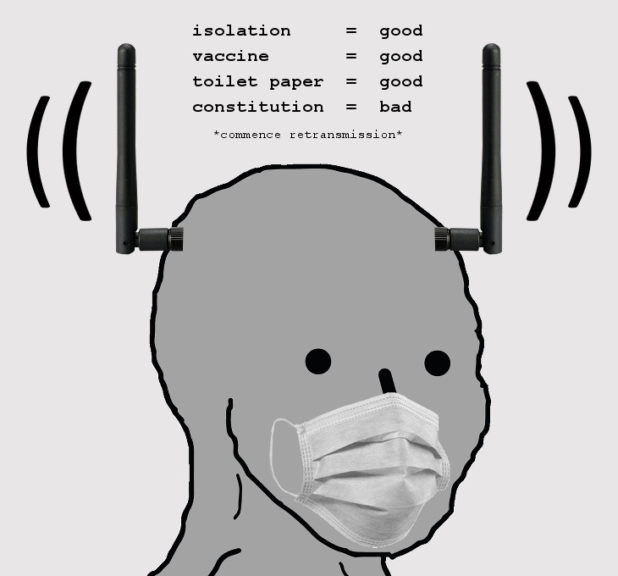

NPC programming command: “USA!” chant is evil. USA evil.

Roger roger.

The article then starts telling a story about how McInnes, once “a tree-planting vegetarian,” an anarchist, and a self-described “dogmatic feminist” went from playing in a punk rock band with anti-Nazi paintings on his chest, to himself becoming the master of all Nazis.

Gavin McInnes in 1989

Early signs of his Hitlerian ways were already visible during his time at Vice.

In 2003, when Vice was largely an extension of McInnes’s psyche, Jimmy Kimmel told The New York Times that its “brand of humor is what I would do if there were no ‘standards and practices’ on TV.” The whole Vice gestalt was so laced with sarcasm that The Village Voice called it “brilliant hipster self-parody.” McInnes’s early provocations were widely perceived as a commentary on hate rather than hate itself. When his stance began to grow more blatantly xenophobic, he turned to stand-up, a medium that allowed him to claim he was only “joking around.” Just kidding had long been his default position. But couching his beliefs in humor didn’t hide the deadly serious nature of his politics. His true intentions were tattooed right on his back—in a tableau depicting a jellyfish with Chiang Kai-shek and Fidel Castro, “two immigrants,” he once proclaimed, “that came into a country, wiped out the previous cultures and started new, prosperous ones…. The days of the West are numbered, and I will be the impetus that destroys it. I am turning America inside out from the outside in.”

By 2016, his unseemly pronouncements had become a part of American political discourse. He made an overt statement on his webcast: “Can you call for violence generally? ’Cause I am.” He also declared, in a textbook example of hate speech, bordering on incitement: “Fighting solves everything—we need more violence from the Trump people. Trump supporters: Choke a motherfucker”—going on to use derogatory terms about trans people and women—“Get your fingers around the windpipe.” The expletive-laden comment was among the reasons he would ultimately get deplatformed from Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and Twitter. In November 2018, he reluctantly stepped down as leader of the Proud Boys. But by then he’d already lit the match and passed the torch. A peer-reviewed Bard College study this year determined that, based on an analysis of his public statements, “the rhetoric spouted by McInnes is actually fascist political action.”

No longer the make-believe insurgent he’d been in his punk days, the Canadian originator of the Proud Boys had become—at 50, his beard specked with gray—a fever-dream incarnate of the tattoo on his back. Not unlike his “good friend” Roger Stone, the Trump crony—and, not incidentally, pardoned felon—who has Nixon’s face emblazoned between his shoulder blades, McInnes wanted to subvert things. He wanted to cause chaos. He wanted to break America—and remake it in his imaginings.

This account, based on my firsthand observations and interviews with McInnes’s friends and former colleagues—as well as McInnes himself—is the forgotten backstory of how a wisecracking media maverick became a well-known and influential “hatemonger,” to quote the Manhattan district attorney’s office.

I worked alongside McInnes at the start of Vice in 1994, becoming the magazine’s editor shortly after it moved from Montreal to New York in 1999. Though McInnes immediately struck me as someone to avoid outside of work, nothing then indicated he would hatch an organization as vitriolic and violence-prone as the street-brawling Proud Boys. He and I were never friends. Founding editor Suroosh Alvi—who remains at Vice Media with the title of founder—brought me on board as a writer at the same time as McInnes. And when I stepped down in early 2001, it was largely because of McInnes’s toxic attitude. (By then his title was cofounder.)

…

At university in Ottawa, McInnes took women’s studies courses and got a ♀ tattoo with an E for equality. He started aligning himself with socially conscious groups. “He did it for social currency—as a fashion statement—rather than because he really believed in the ideology,” claimed Digras. Around that time, McInnes started a punk band called Leatherassbuttfuk with his grade school friend Shane Smith. McInnes sang songs like “You Can’t Rape a .38” as Smith, attired in leather chaps, banged away at a flying V guitar. “They had this weird bondage element,” said Durand, who saw them perform live. “There was blood involved…. Their shtick was being half naked, falling-down drunk. It was fucking gnarly.”

After university, both McInnes and Smith bummed around Europe. Smith relocated to Budapest, where he became, as he’s described it, “a criminal” involved in arbitrage (money trading). McInnes stayed in squats and attended a fascist skinhead rally in Germany. “They look great,” he wrote, shortly thereafter, of the skinheads. “Why is it the bad guys always look cool?”

Oh, there it is.

That’s when Gavin became infected with the White Supremacist virus.

McInnes’s deepening radicalism can be tracked online in a weekly column he wrote from 2008 to 2017 in Taki’s Magazine, the at times far-right-fomenting webzine published by the Greek journalist and socialite Taki Theodoracopulos, cofounder of The American Conservative. Sample titles: “The Myth of White Terrorism,” “Rioting: The Unbeatable High,” and “What’s the Matter With Blackface?” McInnes was recruited to write there by Richard Spencer, who has since become one of the country’s most reviled anti-Semites. “People change and movements evolve,” McInnes told me in one email. “Richard Spencer said ‘Hail Trump’ at that conference and the whole thing went careening off a Nazi cliff…. Spencer was a cool guy. He got me my job at Takimag in 2008 after I left Vice. Back then, he was just some paleoconservative who was obsessed with the founding fathers. The Spencer of today has nothing to do with the guy I knew 10 years ago.”

For his part, the McInnes of today describes his position as “basic dad politics.” He sent me a list outlining his views, saying, “They’re the same views as any rational person.” It included his thoughts on subjects such as “Racism is not a thing,” “America was not built on slavery,” and “Gay marriage is a scam.” His views were openly Islamophobic, transphobic, anti-feminist, and discriminatory toward a variety of groups. One through line: his underlying preoccupation with other people’s bodies, identities, and their realities or personal decisions. When I asked him why he dwelled on that theme, he deflected, as usual: “Proud Boys are unique Americans in the sense that they eschew identity politics.” But as described by the SPLC, “McInnes plays a duplicitous rhetorical game: claiming to reject white nationalism while espousing a laundered version of popular white nationalist tropes.”

McInnes is someone who apparently concluded long ago that white male privilege was imperiled. Come 9/11, believing that his reality was literally under attack, he’d embraced the notion that conservatism was essentially about upholding the status quo for those in power, meaning white men like himself. By 2016, in founding the Proud Boys, he tried to turn his ideologies into political action. Beyond that, McInnes’s overarching philosophy seemed to be that free speech included hate speech. “When you hate someone,” as he once said, “it’s because you recognize something that you hate about yourself.”

…

In terms of my own reportorial interactions with McInnes, when I contacted him after a break of two decades in our communication, he offered to “just jump ahead of all” my questions and essentially interview himself so that I wouldn’t need to interrupt with cardboard-people words of my own. Among his concerns: that nothing he’d said be linked with Nazism. “Everyone keeps coming back to, ‘Are you a Nazi?’ ” he huffed. Nothing could be further from the truth, he insisted.

“I can only imagine it just seems like an unfortunate misunderstanding?”

“It’s not a misunderstanding,” he retorted. “It’s a weapon that people use to try to silence someone else.”

…

Throughout our conversation, McInnes came across as unwilling to take full responsibility for his situation. In his words, he’d simply wanted to “fuck shit up.” He didn’t appear to recognize that statements he has made outlining his ideology are at the root of his troubles.

McInnes’s views have affected his home life. In 2018, ABC’s Nightline interviewed him and his wife, Emily, at their house in New York’s Westchester County, where residents put up signs vilifying him. On ABC, McInnes drank beer as his wife told him, “Your politics having evolved this way in the last few years has been a challenge.” He looked away. Asked whether he was willing to apologize for what he’d created, he said no, firmly. Would he take any of it back if possible? He thought about it, stroking his face roughly. “Yes, I guess, well…. I don’t know.” Then he made a final, dismissive wave. “Nah,” he said, as conclusively as he could muster. It was too late for all that.

…

In our conversation, McInnes struck a genial tone. He said he hadn’t changed much since the time I knew him: “I hated the government; I still hate the government. I want to burn it to the ground.” I asked if he thought the government has him under surveillance. “Oh, they absolutely do,” he replied. “This call’s being listened to right now by the feds. The FBI and the NYPD monitor all my calls and follow all my texts. I’m banned from all social media…. I’ve been de-personed.”

He had a theory on how he’d ended up this way; it went back to eighth grade. “They put me in a special class, even though my grades were okay, because I was just a lot to handle,” he confided. “Eventually, if you keep being provocative, they’ll try to separate you from the rest of the students. And that’s what’s happened on a much grander scale: I’m in the special class right now. That’s the fate of someone who keeps being a class clown.”

I wondered whether he could see the difference between being a clown and inciting violence. Did he know that his actions led him here, that the words he’d uttered had consequences? “I’m not going to deny any culpability here,” he admitted. “I’ve always wanted to kick the hornet’s nest and keep things exciting. But the most recent developments are insane. I didn’t know the hornets would be doing that.”

Some sources I interviewed wondered if McInnes, instead of playing the victim, might take this opportunity to repent or reverse course, no matter how cynically. He did neither. Others were curious if perhaps his parents and loved ones were in a position to help put him on a better path. But when I called his father, Jim McInnes, he was adamant that everything his son had done was a joke, that the media simply didn’t get it. In fact, he said, he’d been writing a book about the whole thing. He even had a title. He was calling it Proud of My Boy.

His dad sounds like a cool dad.