Andrew Joyce

Daily Stormer

April 8, 2018

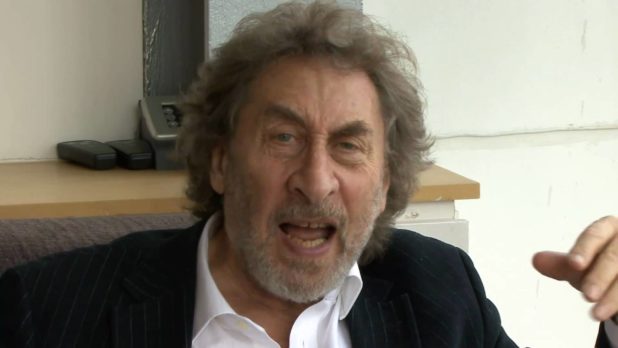

Howard Jacobson, the British-born Jewish author of degenerate literature, has written an interesting piece at The Guardian. Intended to represent Jacobson’s thoughts on the recent moral panic in the British press about anti-Zionist attitudes on the political Left, it inadvertently reveals much about Jewish self-deception and the Jewish persecution complex. That being said, it’s certainly an improvement on his earlier works, such as The Mighty Walzer (1999), a literary melting pot of competitive ping-pong, obsessive masturbation and, more predictably, anti-Semitism. Jacobson opens in a maudlin fashion quite typical of Jewish writers on this subject.

I have been spat at in the street for being Jewish only twice. The first time was in Port Said in the 1960s and I was able to put that down to heightened regional tensions. The second time was 25 years later in Clapham, south London where there were no heightened regional tensions. I knew that I was being spat at for being Jewish in Clapham because my assailant followed the spit with the words, “Now get yourself a shower, and you know what sort of shower I mean.”

I did. I suspect that any Jew over the age of 10 would have known what sort of shower she meant. She. Why her sex surprised me, I can’t say. Maybe I automatically think of antisemites as men.

Jacobson admits “if I am looking to report the pains of being Jewish, these are small pickings,” but adds:

I am touching wood as I say that, for there is no knowing who might do or say what to me next. My superstition, which I don’t think is uniquely Jewish, but certainly has marked Jewish components, warns against tempting fate. It’s not for nothing that there are security men positioned outside synagogues and Jewish schools. We live in a rage-filled, hate-stoked world. And where the hate precedes the cause of hate and only later looks for reasons, the Jew will always do as pretext.

I believe that this is how many Jews view the world, themselves, and the greater span of Jewish history – that the world has always been full of angry, hate-filled out-groups, and that the hatred these out-groups feel is entirely unrelated to anything Jews may or may not do. As Jacobson expresses it: “the hate precedes the cause of hate.” It’s purely an accident that when these out-groups seek to vent their irrational and inexplicable hatred they stumble time and time again on people who just happen to be Jewish.

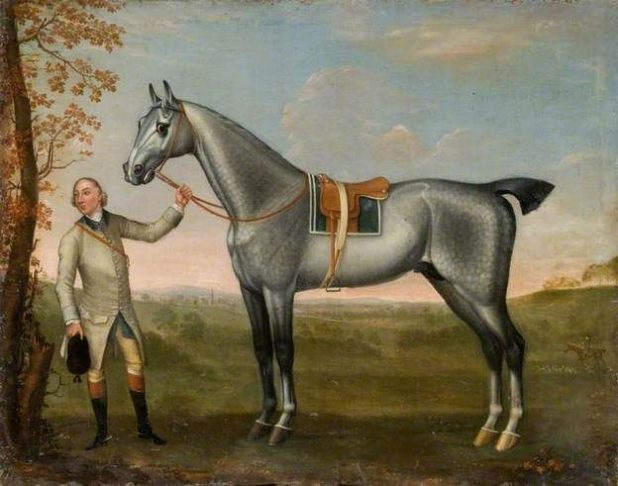

Jacobson then moves on to talk about how he views anti-Semitism – as a form of unprovoked “abuse” which Jews must act against. He briefly discusses violent responses, and then claims his father once knocked out Sir Oswald Mosley’s horse with a single punch:

My father wasn’t averse to using his fists…My father attended Oswald Mosley’s rallies and was once arrested, he claimed, for knocking out the horse the fascist leader was riding. He’d aimed his punch at Mosley and missed.

Like much of Jewish history, this particular anecdote about a horse-assaulting Jew is very problematic, and hides an even more sinister truth. Firstly, I’ve never tried punching a man on horseback but I think I’d require arms several feet longer than I currently possess. I did, for several years, train in Taekwondo – a martial art developed in its earliest form as a means of attacking people on horseback. There are many elaborate and acrobatic kicks involved, but not once was I taught a direct punch. Perhaps this technique is taught in Krav Maga. More seriously, I’ve read countless books written by and about Sir Oswald, and have conducted extensive image searches for anything approaching an appearance on horseback at one of his rallies – there is not a single image or reference anywhere to Mosley riding on a horse in any political or even non-political capacity. However, what we do know is that during rallies held by the British Union of Fascists in the 1930s, the police were often brought in on horseback to maintain order between the BUF and violent Communists. During these clashes, the notorious Battle of Cable Street (October 1936) being an excellent example, the Communists (the vast majority of them Jews) utterly disgraced themselves by attacking police horses. One contemporary witness recalled: “we saw for ourselves the Communists with their clenched fists rolling marbles under the police horses‘ hooves, and stuffing broken glass up their noses to bring the mounted police down, and we were really disgusted.”

We must therefore weigh up the balance of probabilities:

Did Jacobson Snr assault the horse of a man who appears never to have appeared in public on horseback?

Or

Was Jacobson Snr just another vicious Jewish Communist who decided to “fight Fascism” by striking or abusing a beautiful animal utilized by police for peace-keeping, and was arrested by police for doing so?

It was real – in his father’s mind.

I believe that the latter option represents what most probably occurred, although I do believe that Jacobson Snr explained the horse assault to his son in a way that preserved an image of him being on the “good side.” “Well son, I was arrested because I was actually trying to punch Oswald Mosely, but accidentally missed by five feet and got his horse instead.” Telling your child you were arrested for stuffing shards of broken glass into the nostrils of a police horse isn’t normally conducive to an image of heroic fatherhood.

With this particular anecdote out of the way, Jacobson returns to the Jewish mental landscape – a world thickly populated with enemies, and violence just around the corner:

Our parents were still inclined, for themselves, to see enemies everywhere. This was hardly surprising. If they didn’t have their own memories of pogroms and similar acts of anti-Jewish violence in eastern Europe, they remembered hearing their parents relate their memories of them. We forget how many thousands of Jews were slaughtered in that part of the world long before the Holocaust. So antisemitism was bound to be more real to our mothers and fathers than it could ever be to us.

It’s quite fitting, in a way, that the dubious horse attack story should precede this new set of tales – because it’s precisely the same game of “Chinese whispers.” Look again at how Jacobson refers to relatives who, even if they didn’t have memories of pogrom violence “remembered hearing their parents relate their memories of them.” But who is to say that these memories were not, in turn, merely memories of hearing an even earlier generation talk of violence and pogroms? And on and on. In actual fact, the idea of pogroms in the Russian Empire, in which “thousands of Jews were slaughtered” has been utterly debunked. They’ve been debunked not by an obscure “Far Right” think-tank, but by Professor John Klier – a widely respected scholar and non-Jewish former head of the British Association for Jewish Studies who published his findings in a number of volumes via Cambridge University Press (I summarize Klier’s findings here). Among Klier’s findings, the most important of which can be found in Russians, Jews and the Pogroms of 1881-82 (2011) was that the vast majority of pogrom narratives were developed and disseminated by a single Prussian Rabbi – Yizhak Rülf. According to Klier, Rülf specialized in “sensationalized accounts of mass rape.” These accounts would then be disseminated in the Western media with the help of Jewish journalists, and used by groups like the British-based Russo-Jewish Committee to push for Western government ‘action’ against the Tsar. Despite contemporary British government investigations which revealed that no rapes had occurred and perhaps only one or two murders had been committed throughout the Russian Empire, and because most of the general public will never hear about the research of Professor Klier, the myth of thousands of massacred Jews in eastern pogroms remains in the popular consciousness, and is obviously still very deeply embedded in the Jewish folk memory.

Keeping all of this in mind, Jacobson’s last line in that paragraph is especially telling: “So antisemitism was bound to be more real to our mothers and fathers than it could ever be to us.” In reality, Jews have been making this assumption about earlier generations for centuries, and perhaps for thousands of years going back to the Exodus tale itself. Jews excuse their current attitudes by reference to alleged past experiences ,or to the dubious memories of older generations. I’m always startled to observe Jewish discussions of Passover on social media, in which the obviously fictional or allegorical tale of persecution under Pharaoh is taken very literally and emotionally. The same can be said for Purim and the fictional Esther. Jews like those discussed by Jacobson root their current sense of enmity with the world, and sense of danger from it, in past experiences which are largely fictional. Jews like Jacobson, who in their own words confess to feeling surrounded by enemies, feel this way largely because they have subscribed to an identity which requires them to buy into a common narrative of the past – a past in which their group has been the entirely blameless victim of countless unprovoked aggressions. Such conceptions of the self are entirely destructive, leading to obsession and neurosis. Jacobson continues to inadvertently educate us on this very reality by adding, in reference to his group of Jewish school friends: “Antisemitism?” we’d ask darkly when one of us got a bad mark at school, or failed to win a prize, or lost a girlfriend.”

Jacobson still lives in this mental space, and views the current (entirely manufactured) outrage about anti-Semitism on the Left through its lens. He writes that, for Jews like him, contemporary Britain is like being “back in that lightless swamp of medieval ignorance where the Jew who is the author of all humanity’s ills lies, cheats, cringes and dissembles.” Here Jacobson is quite obviously referring to the context of alleged anti-Jewish massacres during the Crusades – a myth which has been debunked by Jewish scholar Robert Chazan in his University of California-published European Jewry and the First Crusade (1996). In addition, the late Alan Dundes, who was one of the world’s experts on folklore, and perhaps the leading scholar of medieval European folklore concerning Jews, never discusses any European belief remotely similar to that posited by Jacobson. (Dundes’ The Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore (1991) is essential reading in this area) In reality, for the last two centuries Jews have exaggerated or distorted historical charges against them in order to discredit the original charge and those making it. Thus, even though medieval Europeans may have been quite clear and specific in their accusations, especially in regards to usury and economic exploitation, they gradually became accused in Jewish history and memory of blaming “all of humanity’s ills” on Jews.

Contemporary Europeans are forced to look on in astonishment at the theft of history itself. Jacobson meanwhile, wrapped up in delusions and seething with frustration, concludes: “And this time there is no horse to punch.”

I’d say you couldn’t make it up – but clearly they do.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History