Oh sure, this makes a lot of sense.

Give people mRNA vaccines for mental health.

The way depression manifested itself in mice in the laboratory of the psychiatrist and neuroscientist Eric Nestler was hauntingly relatable. When put in an enclosure with an unknown mouse, they sat in the corner and showed little interest. When presented with the treat of a sugary drink, they hardly seemed to notice. And when put into water, they did not swim – they just lay there, drifting about.

These mice had been exposed to “social defeat stress”, meaning that older, bigger mice had repeatedly asserted their dominance over them. It is a protocol designed to induce depression in mice, but in Nestler’s lab, it affected some more than others: those with a history of early trauma.

“What one sees clearly in these mouse and rat models is some that are exposed to early life stress do show greater susceptibility to stress later in life,” says Nestler, who is based at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.

This appears to be true for humans, too. The reasons are still unclear, but there is growing evidence that part of the answer lies in epigenetics – processes that modify the function of our genes without changing the genetic code. Many researchers now think that childhood trauma biologically embeds itself in our bodies, alters how our genes work and puts our mental health at risk.

If that thinking holds up, it opens the door to radical new treatments. Just as gene editing is promising new therapies for everything, from heart disease to cancer, there are those who believe tinkering with the epigenome could help us reverse the damage done by trauma – essentially giving us a way to physically edit out the scars of the past.

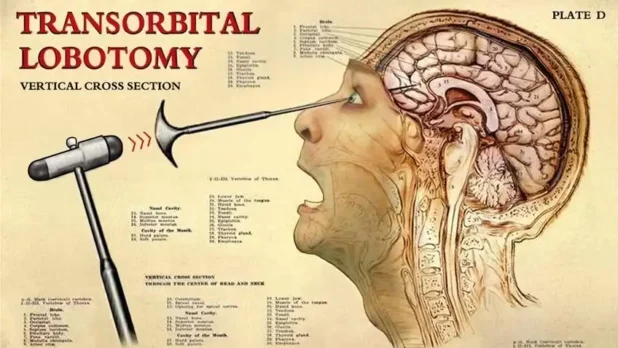

This is kind of like a lobotomy, no?

Very bold strategy for solving the problem of everyone being sad all the time.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History