We’ve got a big scandal with a drug to reduce fatness being pushed on fat retards using unethical marketing strategies.

Hilariously, this methodology of marketing is exactly the same as was used to market Pfizer’s clot shot.

It’s painfully obvious that this is the case, and it’s hilarious that the media is allowed to say the Wegovy marketing was unethical while just not mentioning the Covid shot.

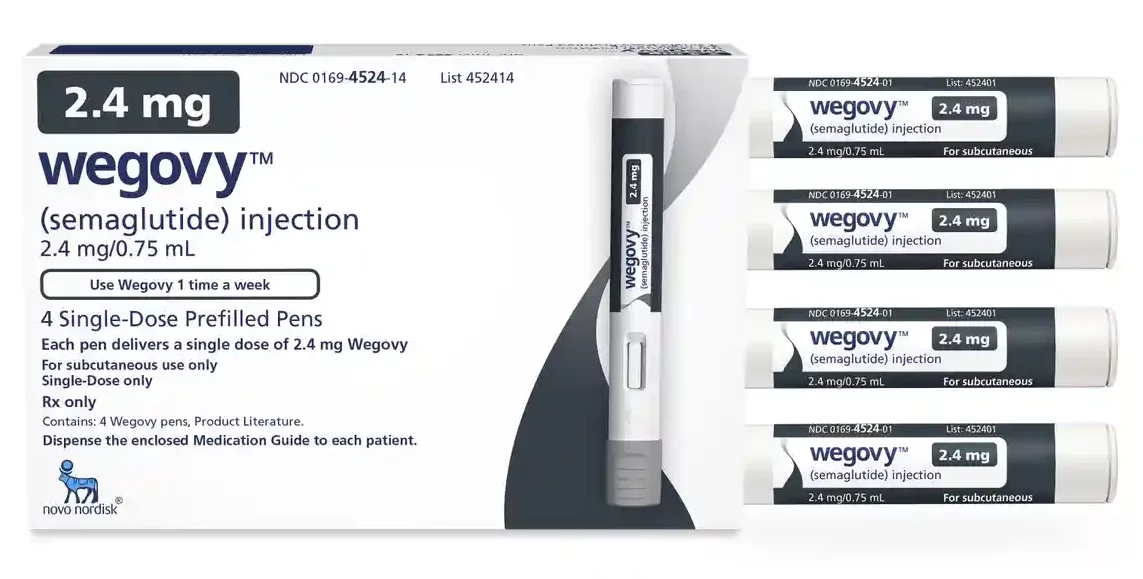

During a prime-time breakfast slot on BBC Radio 4 last week, a leading obesity expert sang the praises of a blockbuster new weight-loss treatment.

The appetite-suppressing Wegovy injections were “one of the most powerful pharmaceutical tools” to date for treating obesity, Prof Jason Halford told the nation.

The problem, he said, would be ensuring enough people could get hold of them.

This was exactly the line used by the media about Covid-19 shots.

Remember, they said people were stealing them, then they came out and said white people weren’t allowed to have them because there weren’t enough, and on and on. It was artificial scarcity on steroids, backed up by media personalities claiming to be concerned.

Halford’s comments were broadcast on the Today programme to millions. But what was not disclosed was that, in addition to his academic work at Leeds University, he is president of an obesity organisation largely funded by the manufacturer of the jabs. Between 2019 and 2021, the European Association for the Study of Obesity received more than £3.65m from Novo Nordisk – equivalent to more than three quarters of its total declared income for that period. Halford was also a previous adviser to the Danish drug maker, sitting on a UK advisory board.

Halford’s financial links to the pharmaceutical company are not a one-off. An Observer investigation this weekend details the millions of pounds paid by the company to experts and organisations in donations, event sponsorship, healthcare training programmes, charity projects, consultancy fees and other payments in advance of its getting approval for use on the NHS.

The 3,500-plus transactions are separate from the company’s spending on research and development, and amounted to more than £21.7m in just three years.

There is now concern about what one expert described as an “orchestrated PR campaign” by the drug company as it sought to shape the obesity debate. It has already been reprimanded by the UK’s pharmaceutical watchdog over breaches of the industry code for another weight-loss drug.

In some cases, organisations and individuals paid by Novo Nordisk went on to be among the most vocal cheerleaders of Wegovy, publicly praising the jabs as a “gamechanger”.

Pfizer was paying not only the entire media, but actually going and paying individual YouTubers.

Then, the government was incentivizing content creators to promote the death jab as well.

And of course, if you questioned it, you got banned.

Thus far, no one has gotten banned for questioning Wegovy.

Others with financial links to the company gave evidence used by medical watchdog the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), providing official submissions recommending the drug’s NHS approval. Despite potential conflicts of interest, the financial links were not always clear.

There is no suggestion the payments broke any rules, and the company says it has never “deliberately acted” outside ethical or legal standards. Recipients of its funding say they were not influenced by it and they properly declared their interests. But critics say the findings raise questions about Novo Nordisk’s attempts to boost its influence across the UK.

More than a quarter of adults in England are obese, and obesity is estimated to cost the NHS £6bn a year.

It’s funny, in America they now just say obesity is healthy.

Actually, this scandal couldn’t even have happened in America for that reason. If an American goes to a doctor and says they want to lose weight, the doctor says “what are you some kind of hater??” Advertising a drug to make you not be fat would be a hate crime in current year US.

Novo Nordisk’s offer of a solution, semaglutide, marketed in the UK as Wegovy, is injected once a week at home. It has been approved for weight loss in the US for two years, where it has won celebrity endorsements, including from billionaire Elon Musk, and has gone viral on TikTok.

Last week, Nice announced that the drug – already available as a diabetes treatment under the trade name Ozempic – had been recommended for use on the NHS. Wegovy will be available in England “soon” to people with a body mass index above 35 and at least one other weight-related condition such as high blood pressure.

Trials of semaglutide have shown that when used alongside diet, exercise and support, it can help people lose up to 15% of their body weight, but there is a lack of long-term trial data on the side-effects. Evidence also shows that when patients stop taking it, they typically regain most of the lost weight. Wegovy’s arrival also comes alongside slow progress in implementing new measures to tackle obesity, such as the government’s long-delayed plan to ban junk food ads on TV before 9pm.

The market for weight-loss drugs is estimated to be worth up to $54bn (£45bn) in the next decade, and Novo Nordisk saw sales of its obesity treatments rise by 84% in 2022 to $2.4bn – a figure it projects will grow significantly in 2023.

But as the company is on the threshold of shaking up obesity care in the UK, there are concerns over what some health professionals say is the “medicalisation” of obesity – and the risk that drug manufacturers’ money may be skewing the debate.

In America, that would mean obesity is not actually a medical problem.

However, in the UK, this means that it’s not something that should be dealt with using medicine, given that it is a problem of diet and exercise (primarily the former, though the latter is related).

It’s nice to see that the UK is not nearly as bad as America when it comes to these issues. I always tend to think of the Anglosphere as more or less just all the same, but this story shows the countries are definitely different, with the UK just not being as extreme and ridiculous.

Transparency records analysed by the Observer lay bare Novo Nordisk’s efforts to foster ties with the health sector.

The payments include donations, event sponsorship, grants and other fees to prominent obesity charities, NHS trusts, royal colleges, GP surgeries, healthcare education providers and universities – on top of £28m spent by the company on research and development. A further £4m in payments such as consulting and lecture fees went to health professionals, including experts on obesity.

The business has also provided financial support for the running of the all-party parliamentary group on obesity – a cross party group of MPs and members of the Lords that lobbies the government on health policy.

In several cases, those paid by Novo Nordisk have played key role in the debate about Wegovy. Two academics who received funding from the company went on to publicly describe the drug as a gamechanger in widely reported comments. Documents from Nice also show that key experts who provided evidence on semaglutide had direct financial links to Novo Nordisk. In two of the three cases, the interests do not appear to have been clearly declared.

Again: this is exactly what happened with the coronavirus shot.

I assume this happened to some extent before that shot, but after it, it’s just an obvious thing that the drug companies are going to use those same methods to sell other drugs.

Why wouldn’t they?

I’m sure Wegovy is safer than the Covid shots. Basically everything is safer than a Covid shot.

One expert who gave evidence to Nice, Prof John Wilding, who leads the clinical research on obesity at Liverpool University, was president of the World Obesity Federation when he recommended Wegovy for use on the NHS. But while his 2021 entry to the conflicts of interest register included his role at the federation, it did not mention the organisation had received more than £4.3m from Novo Nordisk in the three previous years. In addition, he received £19,414 from the company between 2019 and 2021 in “service fees”, work which was disclosed in the interests register.

The World Obesity Federation said it strived to be clear about “conflicts and alignments of interest” and that Wilding had no role in securing its funding. Wilding said he “strongly refuted” the interpretation of his relationship with the company and his role in the Nice decision-making process and had worked hard to ensure “people with severe obesity have access to all appropriate treatments”.

The experts and organisations that received funding from Novo Nordisk said their professional opinions had never been influenced by the money.

But others said the findings showed a need for greater controls on payments by drug companies to uphold transparency and trust.

Haha.

“Others have begun talking like Andrew Anglin.”

Simon Capewell, emeritus professor at the Institute of Population Health at Liverpool University, described the funding as an effort to “buy influence and favourable opinion” that was “totally unacceptable”. He said: “We should be looking at much stricter controls,” adding that the “hyperbole” around Wegovy had been “extraordinary”. “There has been an orchestrated PR campaign, and it’s regrettable so many clinical colleagues have taken part in that.”

Novo Nordisk said it was “proud” to play a role in “vital discussions” to “improve the prioritisation, management and treatment of chronic conditions including diabetes and obesity across the UK”, and it worked in a “transparent and ethical manner” in line with “strict regulatory frameworks”.

“The insinuation that Novo Nordisk has deliberately acted outside of ethical or legal standards and proper processes is unfounded and misleading,” it said.

Ethical and legal standards were thrown out during the fake coronavirus pandemic.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History