Related: Canada: School Board Purges Library of All Books Written Before 2008

Bitch, just do your own art.

Why are blacks so obsessed with theft?

It’s not gotten them anywhere.

Built your own shit instead of stealing!

(Please note that no Indio-Cubans are doing this. Cultural theft, like street mugging, is an activity almost exclusively engaged in by persons of African descent.)

CNN:

Consider Michelangelo’s famous “Creation of Adam,” Sandro Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus” or Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.” When you think of Western art’s grand visual narratives of humanity’s inception — and all its triumphs, beauty, tragedies and meaning — they likely look very White.

This is because, for centuries, the artistic traditions of the European Renaissance have been the authority of such themes. It was from the 15th to 16th century that “art came to be seen as a branch of knowledge,” according to Britannica, “valuable in its own right and capable of providing man with images of God and his creations as well as with insights into man’s position in the universe.”

But Afro-Cuban American artist Harmonia Rosales is among those seeking to radically change this centering of Western ideologies as standard. A selection of her work in this vein is currently on display in the exhibition “Harmonia Rosales: Master Narrative” at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in Atlanta. (A version of the exhibition was first shown last year at the AD&A Museum at the University of California, Santa-Barbara.)

Harmonia Rosales

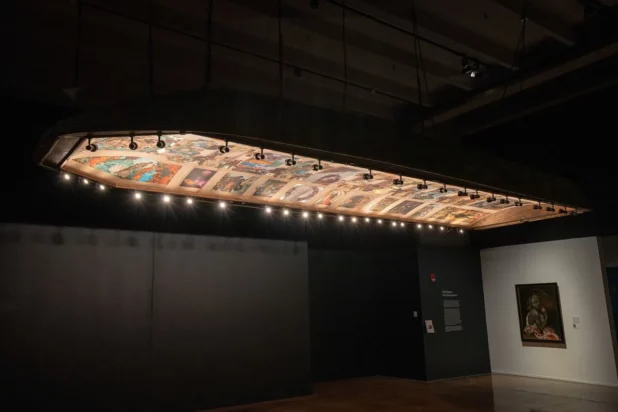

Across 20 oil paintings and a large-scale sculptural installation, Rosales’ work challenges viewers to consider the universality of creation through a Black diasporic lens. The exhibition features seven years’ worth of work, as Rosales entwines the artistic techniques and hegemonies of European Old Masters, focused on Christianity and Greco-Roman mythology, with the characters, themes and stories of the Yorùbá religion.

Yorùbá faith tradition involves a supreme creator named Olodumare and a hierarchy of several hundred deities — orishas — who collectively rule over the world and humankind. Originating in Western Africa at least a few thousand years ago, enslaved people were prohibited from practicing the faith as many White slave masters perceived it as evil, and a threat to the obedience they desired.

Renaissance art largely excluded Black people, even as it emerged during the early phases of the transatlantic slave trade which ultimately brought 10.7 million African men, women and children to the Americas — some 1.67 million of whom were Yorùbá followers.

So why center Black people in an artform that ostracized them, rather than creating an entirely new space to convey this “master narrative?” For Rosales, the best way to diversify the medium is to operate from within its parameters.

“Because it’s what’s been mainstreamed. I’m trying to educate the masses on a religion that has been hidden for quite some time,” Rosales said. “I want to make it very linear, understandable and digestible, so then we can dive deeper.”

“I’m taking the express route of teaching people who they are,” she added. “The only way to do that is by reimagining certain famous images.”

Her exhibition also occurs amid both a broader cultural moment of Black people reclaiming their place in history and owning their heritage, and of pushback against the retelling of this history. Rosales said she doesn’t intend for her work to be utilized as a tool for or against either of these movements, but is happy if it adds to such empowerment.

“Why is seeing us as godly political?” Rosales argued. “Why is adding our narratives — or even trying to alter the story, this foundation that was built and didn’t include us — political?”

“I just see it as, I’m telling something that is part of my culture that I would like to see more of,” she added. “These are my children, and when I let them out into the world, they decide who they want to become.”

Though Rosales initially painted the figures for her daughter, ultimately “I found myself,” she said, “I became empowered about who I am. Every one of these (artworks) tells my stories.”

It’s not who you are.

They’re not your stories.

If you blacks are ever going to have any sort of meaning in your lives, any kind of identity for your culture, you need to create things yourselves instead of stealing from others.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History