Andrew Anglin

Daily Stormer

September 22, 2019

This is like the best new form of converting Christianity into secular Noahidism – “the devil made me do it” is now “my privilege made me do it.”

People in the United States might feel a smidge of schadenfreude at our neighbor’s struggle with a transgression alarmingly common among politicians here at home – if only our own schaden weren’t so tremendous. Still, there’s something about the Trudeau story that makes it especially hard to ignore, and his explanation for his behavior gets right at it.

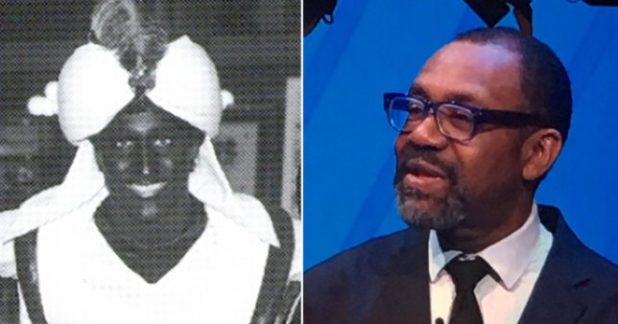

“I came from a place of privilege . . . but now I have to acknowledge that that comes with a massive blind spot,” Trudeau told reporters in the latest of his multiple apologies for his multiple mistakes. “The fact of the matter is I’ve always – and you’ll know this – been more enthusiastic about costumes than is sometimes appropriate,” he told reporters in the first instance.

Trudeau’s critics, of course, have been saying he loves costumes for a long time now. He masks the shallowness of his commitment to the First Nations people with a tattoo based on a Haida design on his sculpted left triceps; he camouflages a retreat from welcoming refugees with a constant flow of lovely language condemning President Trump’s xenophobia.

Yet the trouble with Trudeau’s comment comes not only from casting modern-day minstrelsy as just another “costume,” or even in the coy familiarity Trudeau assumes his audience has with his proclivity for dress-up. No, the trouble comes from the concept that enthusiasm is an excuse – as if Trudeau were a small child who simply could not help himself from dressing up in Jamaican garb and singing the banana boat song, or dressing up as a turbaned character from “Aladdin” for an Arabian Nights party, or dressing up as whatever on earth he’s supposed to look like in the most recently released dark makeup video, because, gosh, it was just so fun!

Trudeau speaks with the bashfulness of a man who expects sympathy from a country that adores him as a father does his little boy. That’s fitting for the scion of a Quebecois dynasty and son of former prime minister, the late Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau. He didn’t do better because he didn’t “know better,” and he didn’t know better because no one ever taught him.

…

It’s obvious what’s wrong with treating the thing that caused insensitive behavior as a reason you expect forgiveness for that same insensitive behavior. Ignorance won’t go away if it justifies itself. There’s a catch, though: Trudeau isn’t wrong.

Trudeau says he “didn’t understand how hurtful this is to people who live with discrimination every single day,” because he doesn’t live with discrimination every day. It’s a cop-out on one level, but on another his words underscore a precept of responsible identity politicking: Check your privilege, the exhortation-turned-cliché goes. It means acknowledge your advantages – both how they’ve helped you, and how they limit you when it comes to comprehending others’ less-charmed lives.

…

What Trudeau teaches us is that there’s a difference between insisting that you didn’t see something and insisting that you couldn’t see something – between blaming your fortunate circumstances for your failure and blaming yourself, then accepting whatever comes your way because you failed.

“I didn’t consider it racist at the time,” Trudeau said, “but now we know better.” There’s the essential question: Do we really?

“I did racism because I’m surrounded by racism, we’re all enveloped by it in the racist controlled world of white supremacy” is the redux of the prince getting caught in a sex scandal and saying “I’m a sinner because we live in a fallen world, we are all born sinners.”

At first when you realize political correctness is all just a reformulation of Christianity, it seems kind of quaint.

But then you see the effects of it, and the goals of it, and realize it is pure evil designed by Jews to exterminate the white race by getting us to go along with new and evil versions of all of these memes we’d previously been familiar with as Christians and which remain deeply embedded in our cultural psychology.