This is the image Reuters used to introduce the article. Don’t worry about that. It’s very normal.

Kids need something and they need something serious: they need to go tranny.

Across the United States, thousands of youths are lining up for gender-affirming care. But when families decide to take the medical route, they must make decisions about life-altering treatments that have little scientific evidence of their long-term safety and efficacy.

On the two-hour drive back from the hospital, Danielle Boyer kept replaying the doctor’s questions in her mind. Was her then-12-year-old child, Ryace, hearing voices? Was she using illegal drugs? Had she ever been hospitalized for psychiatric treatment? Had she ever harmed herself?

Danielle was still shaken when she and Ryace arrived home in this small town nestled in a bend of the Ohio River. Dinner would have to wait. She had to talk to her husband. “They were asking us these sad, terrible questions,” she told Steve Boyer as the two sat in their garage that August 2020 evening. “Do you know kids have tried to kill themselves?”

“I had no idea,” he said.

Ryace Boyer

Ryace (pronounced RYE-us) was assigned male at birth, but by the time she was 4, it was clear to her parents that she identified as a girl. She referred to herself as a girl. She wanted to dress as a girl. But her parents feared for her safety if they let her live openly as a girl in their tightly knit rural community. So they struck an uneasy compromise. At home, Ryace could be a girl, wearing makeup and dresses. At school, around town and in family photos, Ryace would remain a boy.

Ryace chafed at the restrictions. When she started middle school, she grew increasingly anxious about what puberty would bring: facial hair, an Adam’s apple, a deeper voice. That’s when Danielle sought help at Akron Children’s Hospital and its new gender clinic, where staff told her they could treat Ryace with puberty-blocking drugs and sex hormones to help her transition.

“This is what I’ve always wanted,” Ryace told her mother as they left the hospital. Afterward, the pair went on a celebratory shopping trip for girl’s clothes. Danielle was relieved. After years of struggling in isolation to do what they thought was best for Ryace, the Boyers were now getting expert help from people who understood their situation.

But the initial consultation brought troubling new questions. The doctor at the Akron clinic told Danielle and Ryace that puberty blockers could weaken Ryace’s bones. The effects on her brain development and fertility weren’t well-understood. The risk of inaction was even more alarming: Without treatment, the doctor said, Ryace would remain at increased risk of suicide.

Mention of suicide raised the stakes. “She’s been asking for how many years now to be a girl?” Danielle said to her husband as they sat talking in their garage that evening. “We just keep telling her no, and we’re crushing her. If they can help us, let’s do this.”

The United States has seen an explosion in recent years in the number of children who identify as a gender different from what they were designated at birth. Thousands of families like the Boyers are weighing profound choices in an emerging field of medicine as they pursue what is called gender-affirming care for their children.

Gender-affirming care covers a spectrum of interventions. It can entail adopting a child’s preferred name and pronouns and letting them dress in alignment with their gender identity – called social transitioning. It can incorporate therapy or other forms of psychological treatment. And, from around the start of adolescence, it can include medical interventions such as puberty blockers, hormones and, in some cases, surgery. In all of it, the aim is to support and affirm the child’s gender identity.

But families that go the medical route venture onto uncertain ground, where science has yet to catch up with practice. While the number of gender clinics treating children in the United States has grown from zero to more than 100 in the past 15 years – and waiting lists are long – strong evidence of the efficacy and possible long-term consequences of that treatment remains scant.

Puberty blockers and sex hormones do not have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for children’s gender care. No clinical trials have established their safety for such off-label use. The drugs’ long-term effects on fertility and sexual function remain unclear. And in 2016, the FDA ordered makers of puberty blockers to add a warning about psychiatric problems to the drugs’ label after the agency received several reports of suicidal thoughts in children who were taking them.

More broadly, no large-scale studies have tracked people who received gender-related medical care as children to determine how many remained satisfied with their treatment as they aged and how many eventually regretted transitioning. The same lack of clarity holds true for the contentious issue of detransitioning, when a patient stops or reverses the transition process.

The National Institutes of Health, the U.S. government agency responsible for medical and public health research, told Reuters that “the evidence is limited on whether these treatments pose short- or long-term health risks for transgender and other gender-diverse adolescents.” The NIH has funded a comprehensive study to examine mental health and other outcomes for about 400 transgender youths treated at four U.S. children’s hospitals. However, long-term results are years away and may not address concerns such as fertility or cognitive development.

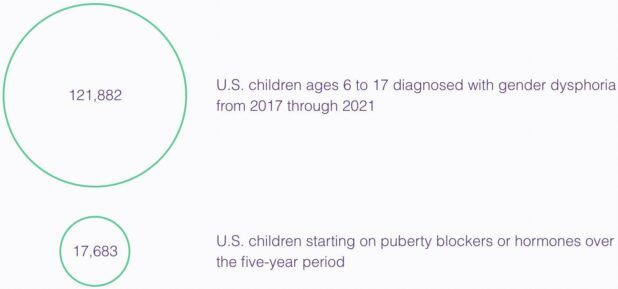

Reliable national data on how many children receive care for gender dysphoria – defined as a feeling of distress from identifying as a gender different from the one assigned at birth – have long been unavailable. To get some idea of the increasing prevalence of these cases, Reuters asked health technology company Komodo Health Inc to analyze its database of U.S. insurance claims and other medical records on about 330 million Americans. The analysis, the first of its kind, found that at least 121,882 children ages 6 to 17 were diagnosed with gender dysphoria in the five years to the end of 2021. More than 42,000 of those children were diagnosed just last year, up 70% from 2020.

Though smaller, the number of children receiving medical treatments like those the Akron clinic outlined for the Boyers is also growing fast. The number of children who started on puberty-blockers or hormones totaled 17,683 over the five-year period, rising from 2,394 in 2017 to 5,063 in 2021, according to the analysis. These numbers are probably a significant undercount since they don’t include children whose records did not specify a gender dysphoria diagnosis or whose treatment wasn’t covered by insurance.

The surging numbers reflect in part the success of years of advocacy for transgender rights, which doctors say has made more children and their families comfortable about seeking help. Transgender children still live with discrimination, bullying and threats of violence. But as transgender identity has become more visible in popular culture, children with gender dysphoria have gained ready access on TV and social media to positive representations of young people who have received professional gender-affirming care.

Gender care for minors gained further legitimacy as medical groups endorsed the practice and began issuing treatment guidelines. Chief among them is the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, a 4,000-member organization that includes medical, legal, academic and other professionals from around the world. Over the past decade, its guidelines have been echoed by the likes of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Endocrine Society, which represents specialists in hormones.

In its latest Standards of Care, released in September, WPATH notes the paucity of research supporting the long-term effectiveness of medical treatment for adolescents with gender dysphoria. As a result, the guidelines say, “a systematic review regarding outcomes of treatment in adolescents is not possible.” The Endocrine Society, in its own guidelines, acknowledges the “low” or “very low” certainty of evidence supporting its recommendations.

The federal government eased the path to treatment in 2016, when the administration of President Barack Obama prohibited health insurers and medical providers from limiting care because of a person’s gender identity. That prompted an expansion of public and private insurance coverage for gender-affirming care, including for children, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars a year for puberty blockers alone.

Today, more than half of states pay for gender-transition treatment through Medicaid, the government health insurance program for millions of low-income families. Nine states exclude youth gender care from Medicaid coverage. Florida, in its Medicaid prohibition, says treatments for gender dysphoria “do not meet the definition of medical necessity.”

That disparity among states is symptomatic of how gender-affirming care has become a flashpoint in the nation’s highly polarized politics.

Many conservatives decry it as a form of child abuse. “You don’t disfigure 10, 12, 13-year-old kids based on gender dysphoria,” Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, a Republican, said at an August news conference, just days before his state banned Medicaid coverage of gender care for children. Alabama, Arkansas and Texas have enacted laws or policies to broadly limit children’s access to care, all of them since blocked by courts. In more than a dozen other states, including Ohio, where the Boyers live, legislators have introduced bills that would ban care or penalize providers for treating children.

At the same time, at least a dozen states, including New York, California and Massachusetts, have aligned with transgender advocates and many medical providers by ensuring that children are guaranteed access to care. And in July, the Biden administration proposed an expansion of the Obama-era protections.

“Gender-affirming care for transgender youth is essential and can be life-saving,” Dr Rachel Levine, an assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said in an interview with Reuters.

Levine, a pediatrician and a transgender woman, drew outcry from conservative opponents of children’s gender care and some medical professionals earlier this year when she told National Public Radio: “There is no argument among medical professionals – pediatricians, pediatric endocrinologists, adolescent medicine physicians, adolescent psychiatrists, psychologists, et cetera – about the value and the importance of gender-affirming care.”

Levine was right, insofar as healthcare providers generally agree that anyone with gender dysphoria has a right to supportive care, whether that entails social transition, or counseling and therapy, or medical interventions. But her statement glossed over deep fissures that have opened within the gender-care community over the way treatment has evolved in the United States as new patients pour into clinics.

A growing number of gender-care professionals say that in the rush to meet surging demand, too many of their peers are pushing too many families to pursue treatment for their children before they undergo the comprehensive assessments recommended in professional guidelines.

Such assessments are crucial, these medical professionals say, because as the number of pediatric patients has surged, so has the number of those whose main source of distress may not be persistent gender dysphoria. Some could be gender fluid, with a gender identity that changes over time. Some may have mental health problems that complicate their cases. For these children, some practitioners say, medical treatment may pose unnecessary risks when counseling or other nonmedical interventions would be the better choice.

“I’m afraid what we’re getting are false positives and we’ve subjected them to irreversible physical changes,” said Dr Erica Anderson, a clinical psychologist who previously worked at the University of California San Francisco’s gender clinic. “These errors in judgment are fodder for the naysayers – the people who want to eradicate this care.” Anderson, a transgender woman who still treats children with gender dysphoria in her private practice, resigned as president of WPATH’s U.S. chapter last year after her public comments about “sloppy” care prompted the organization to issue a temporary moratorium on board members speaking to the press.

In Europe, concern that too many children might be unnecessarily put at risk has prompted countries like Finland and Sweden that were early to embrace gender care for children to now limit access to care. The United Kingdom is shutting down its main clinic for children’s gender care and overhauling the system after an independent review found that some staff felt “pressure to adopt an unquestioning affirmative approach.”

Ranged against those advising caution in the United States are members of the gender-care community who say that denying treatment to any child with gender dysphoria is unethical and dangerous. “You shouldn’t have to jump through hoops to prove your own trans-ness,” said Dallas Ducar, a psychiatric nurse practitioner and trans health provider in Massachusetts.

It’s not even worth responding to at this point.

People just need to know it’s happening is all. If you can’t come up with the obvious response in your mind, you’re too far gone.

Hospital: We give kids puberty blockers and perform double mastectomies on minors.

Conservatives: This hospital gives kids puberty blockers and performs double mastectomies on minors.

The Left: Prosecute & deplatform these conservatives for publicizing the hospital's services!

— Libs of TikTok (@libsoftiktok) October 3, 2022

18-year-old detransitioned woman gave powerful testimony against “gender affirming” model of care that led to irreversible medical transition. Chloe Cole spoke in front of the White House in support of Rep. Greene’s (R-GA) bill Protect Children’s Innocence Act, to shield minors https://t.co/fkdHCvefTu

— Pat Wilkes (@patprays) September 28, 2022

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History