It sure is convenient that global governments are using coronavirus spying mechanisms for regular spying!

No one could have predicted this. If someone did predict it, they were a white supremacist fascist, so their opinion means nothing.

AP:

Majd Ramlawi was serving coffee in Jerusalem’s Old City when a chilling text message appeared on his phone.

“You have been spotted as having participated in acts of violence in the Al-Aqsa Mosque,” it read in Arabic. “We will hold you accountable.”

Ramlawi, then 19, was among hundreds of people who civil rights attorneys estimate got the text last year, at the height of one of the most turbulent recent periods in the Holy Land. Many, including Ramlawi, say they only lived or worked in the neighborhood, and had nothing to do with the unrest. What he didn’t know was that the feared internal security agency, the Shin Bet, was using mass surveillance technology mobilized for coronavirus contact tracing, against Israeli residents and citizens for purposes entirely unrelated to COVID-19.

A worshipper shows a threatening message signed ”Israeli intelligence,” that reads: “Hello! You have been spotted as having participated in acts of violence in Al-Aqsa Mosque, and we will hold you accountable.”

In the pandemic’s bewildering early days, millions worldwide believed government officials who said they needed confidential data for new tech tools that could help stop coronavirus’ spread. In return, governments got a firehose of individuals’ private health details, photographs that captured their facial measurements and their home addresses.

Now, from Beijing to Jerusalem to Hyderabad, India, and Perth, Australia, The Associated Press has found that authorities used these technologies and data to halt travel for activists and ordinary people, harass marginalized communities and link people’s health information to other surveillance and law enforcement tools. In some cases, data was shared with spy agencies. The issue has taken on fresh urgency almost three years into the pandemic as China’s ultra-strict zero-COVID policies recently ignited the sharpest public rebuke of the country’s authoritarian leadership since the pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

For more than a year, AP journalists interviewed sources and pored over thousands of documents to trace how technologies marketed to “flatten the curve” were put to other uses. Just as the balance between privacy and national security shifted after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, COVID-19 has given officials justification to embed tracking tools in society that have lasted long after lockdowns.

“Any intervention that increases state power to monitor individuals has a long tail and is a ratcheting system,” said John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at the Toronto-based internet watchdog Citizen Lab. “Once you get it, is very unlikely it will ever go away.”

…

In Jerusalem’s Old City, tourists sipping fresh pomegranate juice, worshippers and locals taking a shortcut home are all monitored by Israeli security forces holding automatic weapons. The labyrinth of cavernous pathways is also lined with CCTV cameras and what authorities have described as “advanced technologies.”

After clashes in May 2021 at the Al-Aqsa Mosque helped trigger an 11-day war with Hamas militants in the Gaza Strip, Israel experienced some of the worst violence in years. Police lobbed stun grenades into the disputed compound known to Jews as the Temple Mount, home to Al-Aqsa, Islam’s third-holiest site, as Palestinian crowds holed up inside hurling stones and firebombs at them.

By that time, Israelis had become accustomed to police showing up outside their homes to say they weren’t observing quarantine and knew that Israel’s Shin Bet security agency was repurposing phone surveillance technology it had previously used to monitor militants inside Palestinian territories. The practice made headlines at the start of the pandemic when the Israeli government said it would be deployed for COVID-19 contact tracing.

A year later, the Shin Bet quietly began using the same technology to send threatening messages to Israel’s Arab citizens and residents whom the agency suspected of participating in violent clashes with police. Some of the recipients, however, simply lived or worked in the area, or were mere passers-by.

Ramlawi’s coffeeshop sits in the ornate Cotton Merchant’s Market outside the mosque compound, an area lined with police and security cameras that likely would have identified the barista had he participated in violence.

Although Ramlawi deleted the message and hasn’t received a similar one since, he said the thought of his phone being used as a monitoring tool still haunts him.

“It’s like the government is in your bag,” said Ramlawi, who worries that surveillance enabled to stop COVID-19 poses a lasting menace for east Jerusalem residents. “When you move, the government is with you with this phone.”

…

‘360 DEGREE SURVEILLANCE’

Technologies designed to combat COVID-19 were redirected by law enforcement and intelligence services in other democracies as governments expanded their digital arsenals amid the pandemic.

In India, facial recognition and artificial intelligence technology exploded after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s right-wing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party swept into power in 2014, becoming a tool for police to monitor mass gatherings. The country is seeking to build what will be among the world’s largest facial recognition networks.

As the pandemic took hold in early 2020, state and central governments tasked local police with enforcing mask mandates. Fines of up to $25, as much as 12 days’ pay for some laborers and unaffordable for the nearly 230 million people estimated to be living in poverty in India, were introduced in some places.

In the south-central city of Hyderabad, police started taking pictures of people flaunting the mask mandate or simply wearing masks haphazardly.

Police Commissioner C.V. Anand said the city has spent hundreds of millions of dollars in recent years on patrol vehicles, CCTV cameras, facial recognition and geo-tracking applications and several hundred facial recognition cameras, among other technologies powered by algorithms or machine learning. Inside Hyderabad’s Command and Control Center, officers showed an AP reporter how they run CCTV camera footage through facial recognition software that scans images against a database of offenders.

“When (companies) decide to invest in a city, they first look at the law-and-order situation,” Anand said, defending the use of such tools as absolutely necessary. “People here are aware of what the technologies can do, and there is wholesome support for it.”

By May 2020, the police chief of Telangana state tweeted about his department rolling out AI-based software using CCTV to zero-in on people not wearing masks. The tweet included photos of the software overlaying colored rectangles on the maskless faces of unsuspecting locals.

#AI based #FaceMaskViolationEnforcement is being rolled out by TS police.

Leveraging ComputerVision & #DeepLearningTechnique being implemented on surveillance CCTVs across the cities is #FirstOfItsKind in INDIA.

Shall be enabled shortly across the 3Commissionerates

*Hyd,Cyb&Rck. pic.twitter.com/hGwvq9cvsE— DGP TELANGANA POLICE (@TelanganaDGP) May 8, 2020

More than a year later, police tweeted images of themselves using hand-held tablets to scan people’s faces using facial recognition software, according to a post from the official Twitter handle of the station house officer in the Amberpet neighborhood.

Police said the tablets, which can take ordinary photographs or link them to a facial recognition database of criminals, were a useful way for officers to catch and fine mask offenders.

“When they see someone not wearing a mask, they go up to them, take a photo on their tablet, take down their details like phone number and name,” said B Guru Naidu, an inspector in Hyderabad’s South Zone.

Officers decide who they deem suspicious, stoking fears among privacy advocates, some Muslims and members of Hyderabad’s lower-caste communities.

“If the patrolling officers suspect any person, they take their fingerprints or scan their face – the app on the tablet will then check these for any past criminal antecedents,” Naidu said.

S Q Masood, a social activist who has led government transparency campaigns in Hyderabad, sees more at stake. Masood and his father-in-law were seemingly stopped at random by police in Shahran market, a predominantly Muslim area, during a COVID-19 surge last year. Masood said officers told him to remove his mask so they could photograph him with a tablet.

“I told them I won’t remove my mask. They then asked me why not, and I told them I will not remove my mask.” He said they photographed him with it in place. Back home, Masood went from bewildered to anxious: Where and how was this photo to be used? Would it be added to the police’s facial recognition database?

Now he’s suing in the Telangana High Court to find out why his photo was taken and to limit the widespread use of facial recognition. His case could set the tone for India’s growing ambition to combine emerging technology with law enforcement in the world’s largest democracy, experts said.

India lacks a data protection law and even existing proposals won’t regulate surveillance technologies if they become law, said Apar Gupta, executive director of the New Delhi-based Internet Freedom Foundation, which is helping to represent Masood.

Police responded to Masood’s lawsuit and denied using facial recognition in his case, saying that his photograph was not scanned against any database and that facial recognition is only used during the investigation of a crime or suspected crime, when it can be run against CCTV footage.

In two separate AP interviews, local police demonstrated both how the TSCOP app carried by police on the street can compare a person’s photograph to a facial recognition database of criminals, and how from the Command and Control Center police can use facial recognition analysis to compare stored mugshots of criminals to video gathered from CCTV cameras.

Masood’s lawyers are working on a response and awaiting a hearing date.

Privacy advocates in India believe that such stepped-up actions under the pandemic could enable what they call 360 degree surveillance, under which things like housing, welfare, health and other kinds of data are all linked together to create a profile.

“Surveillance today is being posed as a technological panacea to large social problems in India, which has brought us very close to China,” Gupta said. “There is no law. There are no safeguards. And this is general purpose deployment of mass surveillance.”

‘THE NEW NORMAL’

What use will ultimately be made of the data collected and tools developed during the height of the pandemic remains an open question. But recent uses in Australia and the United States may offer a glimpse.

During two years of strict border controls, Australia’s conservative former Prime Minister Scott Morrison took the extraordinary step of appointing himself minister of five departments, including the Department of Health. Authorities introduced both national and state-level apps to notify people when they had been in the vicinity of someone who tested positive for the virus.

But the apps were also used in other ways. Australia’s intelligence agencies were caught “incidentally” collecting data from the national COVIDSafe app. News of the breach surfaced in a November 2020 report by the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security, which said there was no evidence that the data was decrypted, accessed or used. The national app was canceled in August by a new administration as a waste of money: it had identified only two positive COVID-19 cases that wouldn’t have been found otherwise.

At the local level, people used apps to tap their phones against a site’s QR code, logging their individual ID so that if a COVID-19 outbreak occurred, they could be contacted. The data sometimes was used for other purposes. Australian law enforcement co-opted the state-level QR check-in data as a sort of electronic dragnet to investigate crimes.

After biker gang boss Nick Martin was shot and killed at a speedway in Perth, police accessed QR code check-in data from the health apps of 2,439 drag racing fans who attended the December 2020 race. It included names, phone numbers and arrival times.

Police accessed the information despite Western Australia Premier Mark McGowan’s promise on Facebook that the COVID-related data would only be accessible to contact-tracing personnel at the Department of Health. The murder was eventually solved using entirely traditional policing tactics, including footprint matching, cellphone tracking and ultimately a confession.

Western Australia police didn’t respond to requests for comment. Queensland and Victoria law enforcement also sought the public’s QR check-in data in connection with investigations. Police in both states did not address AP questions regarding why they sought the data, and lawmakers in Queensland and Victoria have since tightened the rules on police access to QR check-in information.

In the U.S., which relied on a hodge-podge of state and local quarantine orders to ensure compliance with COVID rules, the federal government took the opportunity to build out its surveillance toolkit, including two contracts in 2020 worth $24.9 million to the data mining and surveillance company Palantir Technologies Inc. to support the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ pandemic response. Documents obtained by the immigrant rights group Just Futures Law under the Freedom of Information Act and shared with AP showed that federal officials contemplated how to share data that went far beyond COVID-19.

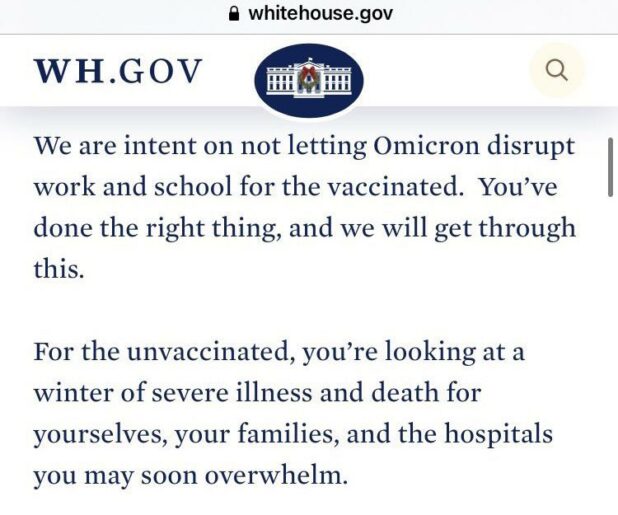

The possibilities included integrating “identifiable patient data,” such as mental health, substance use and behavioral health information from group homes, shelters, jails, detox facilities and schools. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control does not use any of that individual-level information in the platform CDC now manages, said Kevin Griffis, a department spokesman. Griffis said he could not comment on discussions that occurred under the previous administration.

The protocols appeared to lack information safeguards or usage restrictions, said Paromita Shah, Just Futures Law’s executive director.

“What the pandemic did was blow up an industry of mass collection of biometric and biographical data,” Shah said. “So, few things were off the table.”

Last year, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control purchased detailed cellphone location data revealing people’s daily whereabouts, nationwide. “Mobility insights” data from at least 20 million devices could be used to “project how much worse things would have been without the bans,” such as stay-at-home orders and business closures, according to a July 2021 contract obtained by the nonprofit group Tech Inquiry and shared with AP.

The contract shows data broker Cuebiq provided a “device ID,” which typically ties information to individual cell phones. The CDC also could use the information to examine the effect of closing borders, an emergency measure ordered by the Trump administration and continued by President Joe Biden, despite top scientists’ objections that there was no evidence the action would slow the coronavirus.

CDC spokeswoman Kristen Nordlund said the agency acquired aggregated, anonymous data with extensive privacy protections for public health research, but did not address questions about whether the agency was still using the data. Cuebiq did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

For Scott-Railton, that sets a dangerous precedent.

“What COVID did was accelerate state use of these tools and that data and normalize it, so it fit a narrative about there being a public benefit,” he said. “Now the question is, are we going to be capable of having a reckoning around the use of this data, or is this the new normal?”

Of course it’s the “new normal.”

None of these attacks on freedom are ever rolled back.

We’re still living under the Patriot Act, despite the fact that it’s now effectively illegal to talk about Moslems being terrorists.

They could admit the coronavirus never even existed, and they would never roll back these new spying measures.

The good news is: this can only go so far. Eventually, this system is going to be so monstrous and unnatural that it will have to collapse.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History