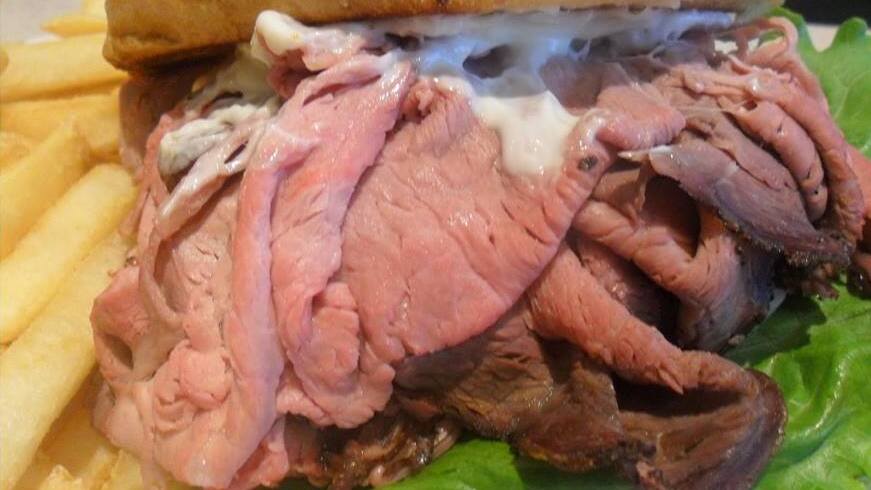

Women used to claim that the “roastie” meme – which claimed that after women have too much sex their vaginas look like roast beef sandwiches – wasn’t true.

Now, they’re admitting that it is true, and are having plastic surgery.

Women are disgusting.

Zoe Williams, who is believed to have a pussy that is completely blown out, writes for The Guardian:

When Florence Schechter opened the Vagina Museum – the world’s first museum dedicated to gynaecological anatomy – in London in 2019, it was partly a response to a dramatic rise in labiaplasty surgery. Instances of such surgery more than doubled in the first decade of this century, then carried on climbing. Zoe Williams, the spokesperson for the museum (who shares my name), says part of the problem is that most women have not seen other vulvas. “Quite a lot of people have never even seen their own, so it’s hard to have a concept of what’s normal. Certainly, throughout art history, the pictures of nude women very seldom had any protruding labia; you just had a neat little cleft.”

Labiaplasty is surgery to alter the appearance of the vulva – generally by trying to reduce the size of the labia minora, the inner genital lips, so that they don’t hang below the labia majora, the outer ones. The reasons for such surgery are not solely cosmetic – they could be related to childbirth, or chafing during sport – yet the rise is staggering. The number of labiaplasty surgeries in 2016 was up 45% on 2015 – the biggest growth of any cosmetic surgery procedure, according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery.

Now, however, a nascent movement is fighting back. It is rejecting the whole idea of genital perfection and reclaiming difference as part of being human – or, for brevity, celebrating what is becoming known on social media as an “outie labia”.

This is most noticeable on TikTok, where Ying Lee (@sativaplath69), who is 24 and uses the pronouns they/them, got a huge number of hits on a post about their “phat coochie” (phat means fat; coochie means vulva), then more still (6.4m) for a witty and complicated piece to camera about “gatekeeping phat coochie culture”.

“When I was making that post, there was a trend of talking about big, juicy coochies,” says Lee over the phone from Vancouver. “And you could apply this to any body part. There was a time when it wasn’t ideal to have big thighs or have a big ass – and then it suddenly was. I guess I get frustrated that women’s bodies are only acceptable when they’re on trend. A trend can normalise you – but only for as long as that’s the trend. And whether you’re in trend or not, you’re still going to have this body.”

Another TikToker, Jennifer Prentice (@jenniferprentice), makes the point deftly that, if you start a conversation about labia with anyone whose labia protrude, “it is like fireworks go off in their brain … I’m not weird? I’m not ugly?” Elsewhere on the site, sincere, social-savvy gynaecologists – such as Jennifer Lincoln (@drjenniferlincoln) and Jen Gunter (@drjengunter), the author of The Vagina Bible – explain the vast spectrum of what is normal, while campaigners share labiaplasty horror stories and myriad women turn the full beam of their scathing humour on a world that doesn’t understand how varied vulvas can be.

It is a movement that is sorely needed. In a poll of more than 3,600 readers, the online women’s magazine Refinery29 found that almost half (48%) had concerns about the appearance of their vulva. Of those, 64% were worried about the size and 60% about the shape of their vulva, with almost one-third (30%) worried about the colour of their genitals. But what is driving this shame and disgust that has become so profound that women have been moved to correct it surgically – and could this bold generation Z labia liberation front overturn it all?

Cabby Laffy, the founder and director of the Centre for Psychosexual Health in London, says it is not a new problem; it is one the late feminist sex researcher Shere Hite pointed out years ago. “Little girls look down at their genitals and they’re told they don’t have them: boys’ are outside, girls’ inside,” says Laffy. This is reflected in confusion around the language of female pudenda at the most basic level – many people say “vagina” when they mean “vulva”. “We don’t name the external genitals,” Laffy continues. “That non-naming is part of the shame, part of the disgust.”

…

Lydia Reeves is a Brighton-based feminist body-casting artist and the author of My Vulva and I, which is published next week. At 29, she is squarely in the digital native generation that has seen enough pornography to remember thinking: “‘Oh my God, that is not what I look like.’ I just assumed that that was what everybody else looked like and I was the only one who looked the way I did. So, of course, I wasn’t going to talk to anyone about it, because that would be mortifying.”

When Reeves started casting women’s vulvas, what surprised her was not the anxieties many had about the way they looked. “I was more shocked by how different everyone’s stories have been, how different their insecurities are. In my naive head, I just assumed everyone’s insecurities would be the same as mine.”

Lydia Reeves

When Reeves was young, she says, there was no such thing as a vulva-positive online community, so she is thrilled that, while such communities are not ubiquitous, “there are definitely those spaces: so many Instagrams, so many people talking about it now. I’m hopeful that we’re turning a bit of a corner.” She is keen to underline that pornography was not the problem, per se – it was that there was no visual or cultural representation other than the very particular aesthetic of pornography.

As Reeves has seen first-hand, there is a lot that women can hate about their vulva, from the relative difference in size between labia minora and majora (56% of women have visible minora, but often this is why they think they are abnormal) to shape, colour, shade and a tautness that doesn’t make sense in labia, but some people (pornographic actors) embody nonetheless.

The artist Jamie McCartney produced The Great Wall of Vagina – 400 plastercast vulvas – in 2011, five years after starting the project. He was inspired by a previous commission to create art with male and female genitalia for a sex museum. (He knows that the casts he has made are of vulvas, not vaginas, but the word play doesn’t work so well.)

The Great Wall of Vagina

McCartney says: “While casting, I discovered that loads of women had anxieties about their vulvas, particularly their labia. They would look at other casts and say: ‘This one’s so neat,’ or: ‘I wish mine looked more like that.’ I was incredulous – there really wasn’t any sense in my mind that some were good and some were defective. And this ideal was created in my name, apparently, because that’s what men like. I just thought: ‘Fuck that.’”

…

What is the impact of such a negative self-image combined with shame? Laffy suggests it is that you will get less from sex. She uses a food analogy to make the point: “If you’ve got shame and difficulty connected around foods, it’s hard to take pleasure in them.”

There it is.

That’s why women should be made to feel bad about the appearance of their genitals.

The more labia-shamed they are, the less likely they are to enjoy sex. The less they enjoy sex, the less likely they are to engage in casual sex with strangers.