Activist protesting against censorship in Kiev.

Here I thought that the media had already been totally shut down in the Ukraine. But they’ve found a way to shut it down even harder by blocking all websites they disagree with.

RT:

While fierce battles continue to rage between the Ukrainian and Russian armies in Donbass, Kherson Region, and Zaporozhye, the Kiev regime is busy eradicating the last vestiges of freedom of speech in the country.

On August 30, Ukraine’s rubber-stamp parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, passed a bill on the media at the first reading. Despite the numerous changes that the 300-page document has undergone since President Vladimir Zelensky’s team developed and submitted it a few years ago, its essence remains unchanged. If it becomes law, the authorities’ power over virtually all outlets will be essentially limitless.

The main danger this bill presents is that it grants government agencies the authority to block internet resources without any court proceedings, and revoke licenses from broadcast and print media solely on the basis of complaints. This huge power would be vested in the National Council for Television and Radio Broadcasting.

No room in the EU

Ukrainian journalists have been criticizing this bill since the first version appeared in 2018, asserting that it abolishes both freedom of speech and freedom of the press. OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Harlem Desir called that version of the law “a blatant violation of freedom of speech,” stating that its adoption “could jeopardize pluralism in the media market, impose additional costs on the media, and negatively affect the reflection of a diversity of ideas and opinions.”

Criticism of the bill from both the OSCE and Ukrainian journalists had an effect. In 2020, it was sent for revision, but the changes only include some clarifications concerning gender equality and coverage of sexual orientations.

At the same time, it still contains a ban on publishing any messages contradicting the official government line on military issues. It is likewise forbidden to cover speeches made by officials of the ‘aggressor country’ [meaning Russia] or cast former USSR party functionaries in a positive light. For example, including Ukraine’s own Leonid Brezhnev.

The law would also hold foreign media responsible for any of its audiovisual content available in Ukraine. Moreover, social networks, including foreign ones, will be obliged to remove any material the National Council deems undesirable. The deadlines for removing ‘incorrect’ content or replacing it with ‘correct’ material have also been tightened. Among the ‘offenses’ that can get a media outlet banned is distributing programs in which any participant is on the ‘list of persons who pose a threat to the national media space of Ukraine.’ This is compiled by the National Council itself and does not require anyone’s consent.

Journalists protest in front of the Cabinet of Ministers in Kiev.

Otherwise, the essence and spirit of the bill is preserved, including severe censorship of “objectionable” media. The American Committee for the Protection of Journalists (CPJ) didn’t call on the Verkhovna Rada to reject Bill No. 2693-D ‘On Media’ for nothing.

Maya Sever, president of the European Federation of Journalists, has bluntly stated that it means compulsory media regulation “fully controlled by the government worthy of the worst authoritarian regimes.” She is convinced that “a state that would apply such provisions simply has no place in the European Union.”

…

Although the Ukrainian media has always had to fight the authorities’ attempts to restrict its activities, it was the Western-backed 2014 Euromaidan that triggered systematic persecution of press freedom in general, and individual journalists in particular.

Less than a month after the coup the new government tried to close down one of the two most widely read Ukrainian weeklies specializing in news analysis, ‘2000’, which took a negative view of the political forces that had violently seized power. The newspaper’s editorial offices were ransacked, and many left-wing outlets were shuttered. In particular, these included Borotba, as well as Rabochaya Gazeta, whose editor-in-chief ended up in the dungeons of Ukraine’s secret police, the SBU.

In the same year, Konstantin Dolgov, the editor-in-chief of ‘Glagol’, an online publication based in Kharkov, and Andrey Borodavka, a journalist, were arrested and persecuted by the new authorities. Olga Kievskaya, editor-in-chief of the ‘Anti-Orange’ website, was forced to emigrate due to threats to burn her face with sulfuric acid. Meanwhile, Borotba journalists Andrey Manchuk and Evgeny Golyshkin were attacked by Maidan activists, and another journalist, Sergei Rulev, was captured and tortured in Kiev in March.

Kiev reporter Alexander Chalenko, well-known analyst Rostislav Ishchenko, and Orthodox journalists Dmitry Zhukov and Igor Druz were all forced to leave Ukraine immediately after Euromaidan due to threats to their lives. Konstantin Kevorkian, director of Kharkov’s First Capital TV company, was expelled from the National Union of Journalists for dissent and arrested, while Valery Kaurov, editor-in-chief of Orthodox Telegraph, an Odessa church newspaper, fled abroad due to criminal charges of ‘separatism’ that have become standard in today’s Ukraine.

The vast majority of these cases were not covered in the Ukrainian media because these people were immediately declared “subversive elements” based on the so-called “moratorium on criticism of the authorities,” which the authorities announced themselves back in March of 2014, long before the start of hostilities in Donbass.

In 2018, Igor Guzhva, the head of the ‘strana.ua’ website, was forced to flee to Austria, where he received political asylum. The authorities’ efforts to prosecute him began after his investigations into Pyotr Poroshenko’s scandalous commercial activities. Later, under Zelensky, Ukraine imposed personal sanctions on Guzhva, and his website was blocked extrajudicially, while he himself, along with one of his journalists, Svetlana Kryukova, were entered into the ‘Register of State Traitors’. According to the head of Ukraine’s Union of Journalists, Sergey Tomilenko, these sanctions are political, and the European Federation of Journalists issued a statement condemning these actions as “a threat to the press, freedom, and media pluralism in the country.”

But not all Ukrainian journalists managed to emigrate, even after surviving prison. In April of 2015, the famous Ukrainian writer-historian and journalist Oles Buzina died at the hands of ‘Patriots of Ukraine’ after receiving threats and attacks due to his views. Despite appeals from the UN, the authorities have hampered the investigation in every possible way, and the murder suspects are still at large, evidence notwithstanding. In July of 2016, another journalist, Pavel Sheremet, was killed by participants in Kiev’s ‘Anti-Terrorist Operation’ (ATO) and supporters of the “purity of the white race.”

“Government critics, journalists, and non-profit organizations have come under increasing pressure from the authorities and far-right groups, which have embarked on the path of infringing freedom of speech and freedom of association under the pretext of countering Russian aggression,” Amnesty International said in a 2017 report.

Remember: we’re being told that the Ukraine is the only democracy on earth and that we must fight for their great freedoms. But they have more censorship than Russia. According to many people’s definition of democracy, the annexed regions have more democracy now. At the very least, they have more freedom.

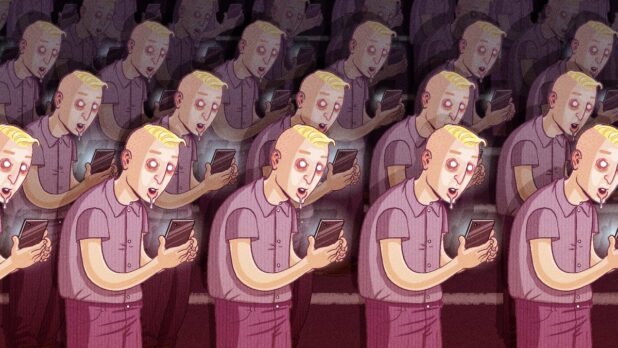

Pictured: a successful democracy.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History